We like to think of history being driven by New Yorkers, but it is dominated by the harbor.1 Not to brag, but New York is one of the greatest natural harbors in the world.2 Amongst the tri-state coasts,3 you have the Hudson River running between Jersey and Manhattan, feeding into New York Harbor, which can also be called Upper New York Bay. It’s connected by the Narrows to Lower New York Bay, which is, true to the name, a bit to the south and includes Raritan Bay off Jersey, and to the Long Island Sound by the East River.4 Just as the city has come to be known as place where disparate communities come together,5 New York Harbor is an estuary where salt and fresh water rush together to create something new. Its islands tend to define the city but let us take a moment to consider the entire metropolis beneath the currents that surround us and the noble, delicious creatures that shaped the waters that shaped us: the oyster.6

There is fossil evidence for oyster-ancestors going back 520 million years to the Cambrian period7 and they evolved into what we might recognize as oysters8 around 65 million years ago. There are shell beds in New York going back 10,000 years9 and Dobbs Ferry boasts the oldest shell pile that dates to around 6950 BCE.

Oysters are all from the family Ostreidae. Not to play gatekeeper but that’s the definition: if it’s not from the family Ostreidae, it’s just sparkling shellfish.10 They have distinct shell halves: a deeper, curvier side called the bottom, or the left shell, that lets the oyster rest in its own liquid and a flatter side that’s the top, or right shell. It has a foot that it uses to affix itself to an object, be it rock or pottery shards or other oyster shells, and will grow asymmetrically around its new home.11 It’s by putting one little oyster foot in front of another that reefs are formed. This is what makes oysters a keystone species, since the reefs built up by layer upon layer of shell and stone attract other species and become a habit for hundreds of their underwater neighbors12 and that’s on top of filtering the water and keeping oxygen levels balanced. The oyster beds around New York would have covered around 220,000 acres. New York City as it stands now is around 193,700 acres, so point to the oysters on this one.

Oysters eat plankton and do so by letting water flow through their open shells, which ends up meaning between twenty and fifty gallons of sea water a day getting filtered in the process. They take in silt and algae and particulates as well as plankton, coating the less desirable elements in mucus bubbles. These are a bit brown and lumpy for jewelry, but scientists can actually use those mucus waste products to measure the biodiversity of the water.13 Speaking of the multitude of life you find in the water, oysters will snap their shells shut by their hinge if they sense danger but they can’t eat that way, which means oysters always chew with their mouth open. And to confirm what you might be thinking from realizing they can sense danger, oysters do have a nervous system. The other giveaway in that line is that they have a lot of predators: snails, some flatworms if the oyster is still very young, star fish, crabs,14 storms, and eventually pollution. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves and our oysters.

A female oyster, which kind of means any oyster as they can change their sex,15 can have ten million eggs that spread out under water in the hopes of crossing paths with a nice sperm ball. If it’s successful, the egg becomes a trocophore and then a larva, just swimming around and looking for calcium to cling to. After around three weeks, its eye and foot pops out and it attaches to something and it’s called a spat.16 And then it just grows. It takes around a year to reach adulthood but oysters will keep growing as long as the water they’re in stays over 41 degrees Fahrenheit. That, consequently, is why there’s a size difference in oysters along the East coast: the Eastern seaboard is home to the Ostreidae Crassostrea virginica,17 but because of differences in the water18 and temperature, they can taste and look different.19 More southern oysters can grow bigger and may have a more subtle flavor where northern oysters20 will stop growing sooner but have a stronger and brinier taste. They can live for about ten years if nothing interferes.

Humans have been eating oysters for 164,000 years. Greeks and Romans loved them. The British loved them. The French loved them. And the Lenni Lenape loved them.21 I’ve been calling it New York City but the land22 we’re talking about is also the Lenapehoking. Lenni means “real” or “original” in Munsey and Lanape translates to “The People” and the fishing villages, farms, and hunting terrain of the Lenapehoking23 covered what we currently call New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and parts of Pennsylvania. Like a lot of large nations, the Lanape are diverse but linked by common practices and a common language. The Canarsie, the Rockaways, and the Massapequas speak Munsey.24 The Raritans,25 the Tappans, and the Hackensacks are Unami-speaking tribes, which is in the same linguistic family. It's hard to pinpoint the exact population, but there were probably around 12,000 people living in fishing villages off the Delaware and Hudson rivers when the Europeans arrived,26 but that’s working backwards from there being around 3,000 Lenape in 1700.27

I mentioned fishing villages because we’re talking mainly about a bunch islands and the rivers and straits that love them, but the Lenape carried oysters—and oyster shells—inland using the natural waterways as highways. The thing about shell piles is they don’t rot, so we can find them all over28 the place, with piles being uncovered in the Rockaways and Inwood throughout the 1800s, on Liberty Island, and all the through the 1980’s during construction for the Metro-North. Sometimes those piles answer concerns by being a pretty solid building material for roads and sometimes the older shell piles raise questions, like how the Lenape were eating the oysters because the shells weren’t broken.29 The other lovely issue raised about ancient shell piles is oysters aren’t actually the most effective nutrition in the area. With rivers full of fish and land running over with game, oysters are a lot of work for a limited mathematical payoff. You would need to eat around 250 a day to get the calories you need to live. Which means people ate them because they liked them. I just think there’s something nice about the rich history behind having just a little treat.

Oysters were not the only shell game in town, but some clam shells were separated and used as currency.30 In addition to building blocks, cash and fertilizer, knives and tools could made from the shells. There were more than one kind of shell pile: shells that were discarded from oysters that were eaten fresh, called kitchen middens, and shells that were used to preserve food for winter months, which were processing middens.

There was a shell heap point around what’s now Center and White Streets, around Kalck Pond31 in the wetlands of lower Manhattan. Speaking of Manhattan, that name also comes from the Munsey, though there’s some disagreement on if the origin is “manahatough,” “a place where wood is available for making bows and arrows,” or “manahactanienk,” “place of inebriation.”32 Some people throw out the possible root as “menatay,” which means “island” but considering how many islands are floating around the bay, that seems pretty vague. Like if you’re in New York and you say to someone to meet you on the island, I’m sorry but you’re not finding that person: you’re going to spend your time crisscrossing each other on ferries and trams because one person is in Brooklyn, then Roosevelt Island, than Governors Island and the other is zipping from Manhattan to Staten Island and chartering a boat to North Brother Island.33 And that scenario is the basis for a rom com, not effective nomenclature.

The other Munsey word relevant for the moment is “shouwunnock,” or “Salty People,” which is what the Lenape called the Europeans who plowed into the Lenapehoking looking for a waterway to China. The first serious encounter with Europeans was the arrival of Henry Hudson, an Englishman working for the Vernenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or Dutch East India Company,34 though Portugese explorers Giovanni da Verrazzano and Esteban Gomez had breezed by a generation before. Hudson sailed into Delaware Bay before landing on Staten Island. He described the indigenous people as polite and not to be trusted, which feels a bit like an accusation that’s really a confession. The Dutch waxed poetic about the beauty of the land and the plenty of the sea, enthusiastically listing new species of fish and proclaiming a disproportionate number of them to be aphrodisiacs.35

New Amsterdam, as the Dutch West India Company deemed it,36 was intended as a trade outpost rather than a colony. Beaver pelts were high on the list because they were so in demand in Russia that beavers there had been hunted to near extinction.37 There was some early hope that they’d have a cache of pearls to harvest, but the waters were full of oysters not pearl oysters and they didn’t need to see how they connected to rocks and calcium sources to see what was being produced by the local oysters was kind of brown and distinctly un-gem like.38

This is more of a risk of understatement than spoiler, but the Lenape and the Dutch traders did not really get along. They traded sometimes and fought other times but they were operating under fundamentally different understandings of the world and how individuals relate to the land they reside on. The most famous example is the question of whether land is something you own: the Dutch and the Lenape had different answers. The Dutch said “yes, for sure, and in fact we won’t do a lot of building until we get a bill of sale” and the Lenape said no: land was something you could use and offer tribute to access and forge alliances but it was not a possession.39 The “oh my gosh, can you believe they sold Manhattan for $24 worth of BEADS?!?” version of the story is super condescending and infantilizing and just very racist in a “they had it coming” kind of way. If beads are money, yeah - that’s what you trade for stuff. Sometimes I trade scraps of old paper for food and alcohol. That’s how cash works.40

So, paper in hand even if all parties involved didn’t agree on what was actually at stake, the Dutch started building New Netherland over Lenapehoking. New names started getting written into the maps: Minnissais Island became known as Great Oyster Island,41 and Kioshk, or Gull Island, became Little Oyster Island.42 A waterfront street by a particularly large shell pile was renamed Pearl Street.

It would eventually be paved with shells,43 but that would be later. And Mother-of-Pearl Street might be more accurate, albeit harder to fit on a sign, since the coating that makes a bead that rich people wouldn’t wear as jewelry is made from a calcium-carbonate called argonite and a protein called conchiolin, which together form nacre, or mother-of-pearl. If language is one way a people rewrite a history in their own image, Pearl Street would see another as well: food. Pearl and Broad Street became a destination for finding beer and oysters, which you could find served stewed, as a sauce, fried, rolled in cornmeal, pickled, with gravy, with wine and citrus, and on toast with anchovies and parsley. The Dutch brought a lot of their traditions with them and then adapted them for wherever they were empire-building, which is why so many nations they traded with or conquered have a rose cookie.44 The Dutch high ideal of tolerance did also make it over to New Amsterdam. By the 1630s, there was a thriving free Black community in what we know as the West Village. New Amsterdam was a place people not in the in-group45 could go and live and actually have full citizenship and worship freely, even the unpopular religions.46

Where they fell violently short was with the indigenous residents of Lenapehoking. Relations had never been great despite some Dutch legislative reminders not to cheat or injure the Lenape47 and was made horrifically worse when Willem Kieft was made director of New Netherland in 1638. Kieft started his career as a merchant but made a name for himself by saving the Dutch West India Company a lot of money by letting hostages rot rather than pay a high ransom. His main legacy was ordering the massacre of the Wieckquaesgeck in Corlears Hook in what’s now the Lower East Side. Everyone was slaughtered, even children. The brutal act of aggression started a war, and effectively weakened New Amsterdam past sustainability. He was fired in 1647 and, like a genocidal Poochie, died in a shipwreck on his way back to Amsterdam.

New Amsterdam was losing money, and it was there to help make money. To steady the ship and staunch the (sometimes literal) bleeding, the Dutch West India Company appointed Peter Stuyvesant as governor. He tried to sober up the island a bit and mandate the observation of Sabbath. He also tried to ban Jews (unsuccessfully) and would pretty loudly complain about atheists and all the languages spoken in the markets. It was under his tenure that the in 1653, a wall was built along the border of the Dutch settlement out of concern of encroaching British colonies.48 The Dutch started dumping trash over wall in an “out of sight, out of mind” moment, much of which found its way into the rivers, as did the sewage that ran through the canal that we know as Canal Street.49

Anyway, you know who also loved oysters and land and had already forcibly claimed a lot of the land to the north and south of New Netherland? The British. They basically sidled up to the wall and made a “we can do this the easy way or the way with the cannons” offer. Stuyvesant was ride or die for the Dutch West India Company but a bunch of citizens50 petitioned that they would rather live as Brits than die as Dutchmen, so New Amsterdam became New York in 1664. Some things changed under the new flag, and some didn’t. Both the Dutch and British had leaned on harvesting oysters by hand at low tide, which was fine if you just wanted an oyster as a little treat but was not a scalable answer for commercial fishing. The Lenape used a tool called tongs, but long rakes soon made larger and larger hauls feasible and some oystermen found success with 16-foot tongs. Oyster shells were still used in wheat fields as fertilizer but there was an ordinance in 1703 that banned shells being burned to make lime for mortar within half a mile of the city because it smelled bad in a way people thought was unhealthy. Since, as a British colony, the British had first dibs on New York’s goods, a lot of pickled oysters were sold within the Triangle Trade, as America selling surplus food to places like the West Indies left plantations free to put their farmland to sugar fields. And the oysters kept rolling in all over.

Some conservation measures started cropping up as early as 1679, though they were haphazard and often highly local. In 1715, a ban was passed against harvesting in summer months.51 Staten Island and then New Jersey in retaliation said only residents could rake oysters in their waters. Rockaway had rules about paying the township to harvest there, a shilling per thousand oysters. Raking oysters just to burn for lime was banned.

You could still see the oyster beds from the city, though, and in 1772 over half a million New York oysters were being sold. Many were bought fresh off the sloops to be pickled and resold. Oysters were prized but they weren’t luxury items: poor and working class New Yorkers would eat bread and oysters multiple times a week. In 1763, the first oyster cellar opened on Broad Street, right by the area that had been an oyster destination in Dutch New Amsterdam. Oyster cellars were marked by a red globe lamppost over the stairs, which reads a little Out of Service Subway STation to me, but the cellars had the subway beat to the underground by 141 years, so what can you do. You’d also find oysters sold on the street and in taverns. By the time the Continental Congress was getting ready to declare independence, the tavern population had bounced back after the rule of Peter Stuyvesant even if the oysters were still suffering. Relatedly, there were also a lot of prostitutes.52 I say relatedly because a not-insignificant number of oyster cellars had rooms in the back for short term rentals, if you follow.53 As for other economic impacts: a good oystermen could clear as much as the equivalent as $100 a day.54

This was not a great period for public health regulation or smells.55 Sewage was still getting unceremoniously dumped into the river where people swam and fished and where the oysters were eating, first carried by enslaved Black Americans and then starting in 1796 by underground pipes. The public food markets established in 1699 with strict quality control started falling into disrepair until an 1843 court decisions deemed the high standards and strict controls on the selling of meat “unlawful interference with free enterprise.”56

As we had just won the revolution but not yet won the War of 1812, America was no longer selling pickled oysters to British colonies because Britain banned trading with America57 but an artist-turned engineer from Pennsylvania was about the make sure that was a non-issue.

In 1807, Robert Fulton demonstrated the speed and reliability of steamship travel to New York state.58 Suddenly, a trip from New York City to Albany meant half a day of travel instead of a full week, which is a massive sea change59 for both passengers and cargo. Now, New York was sending fresh oysters to Europe and not able to keep up with demand even when with Long Island, Connecticut and New Jersey getting in on the action. Not unrelatedly, also in 1807, the conservation law banning harvesting in summer months was suspended. In 1817, ground was broken on the Erie Canal, proposed by an upstate politician named Joshua Freeman and brought to being by New York City mayor and New York state governor and just Very Tall Man, DeWitt Clinton. It wouldn’t be finished until 1825, but it opened in stages and was popular every step of the way. Following that, 1819 saw New York City’s first cannery open for oysters and codfish. Even without pickling and preservation, oysters had thick shells and came packed in their own liquid as long as you pack them left side down, which meant that they could survive a trip west. Truly, the world was the oyster’s oyster. For now.

Oyster beds off Staten Island were already in trouble by the 1810’s, so oystermen started cultivating reefs, hoping necessity would be the mother of invention and, like oyster mother, lay millions of eggs in one go. Some lessons were learned from French marine biologists and fishermen, as they were endeavoring to protect their own beds, and some lessons were born out of experimentation. In Staten Island, this meant growing oysters in Great South Bay where the water was too fresh for oyster drills60 and then transferring them to West Bay, which had saltier water and so produced a more flavorful oyster. Staten Island oystermen also brought in spats61 from Chesapeake Bay, which had a faster growing period since the water was warmer. They would also use pottery or old oyster shells to help promote a friendly environment.

This was all a mix of conservation and concern but also using scientific progress to counter the symptoms our own greed and short-sightedness rather than addressing the root causes. It didn’t help that the government was slow to put laws into place around cultivation, and oystermen worried about the expense of bringing in Chesapeake spats that someone else might try to harvest. So much of the prevailing assumption had been if oysters are there, there should be harvested.62 Cultivators could now lease beds from the state as long as they weren’t coopting wild reefs that could potentially be fished. It did help that cultivated oysters didn’t have the same issues we associate with farmed fish, since oysters live a pretty plant-like life even when they’re wild. It did mean smaller oysters, though, since cultivators didn’t want to use their time on long growth periods. Cultivators spread out oyster shells just before the free-floating babies were ready to attach so the starter-reefs wouldn’t get slimey and become unappealing to spats looking for a home. Oystermen would often dredge to clear the bed for harvesting or just to have a fresh start. Dredging under sail power had been one thing, but now there was steam power behind it and the force of it was too much.63 There were some bans and partial bans64 against dredging in Jersey, and Great South Bay banned dredging in 1870 but then repealed the ban in 1893. There was never any crescendo of progress; there were sidesteps and backslides all over.

But let’s trace the spats back the Chesapeake Bay for a moment. We’ve spoken of Indigenous and European oystering traditions but there was also a long history of oystering in Africa that kidnapped Africans brought with them when enslaved. A lot of the oystermen coming up from Maryland with spats to plant (and sometimes just for work) were free Black men. Maryland was a slave state with a formidable free Black population, but a lot of restrictions on what they could do and how they could live: Black men were not allowed to own their own sloop, or captain their ship without a white man around. New York and New Jersey had been the only northern states that didn’t free their slaves immediately after the revolution, but emancipation was in progress and there were rights one could take hold of in the interim, like your own ship, your own oyster bed, and maybe a vote.65 Additionally, Black oystermen traveled with a Seaman’s Protection Certification66 which served as an ID that could be traded if someone need a way out of the south. This made for a surprisingly integrated industry in the years before the Civil War, but it also made for thriving Black communities, like Sandy Ground in Staten Island.67

New Yorkers were building lives and New York was building name for itself on the back of oysters, but there wasn’t much of a fancy food scene68 until a Swiss immigrant named Giovanni Delmonico parlayed his experience as a wine merchant and his brother’s skill as a pastry chef into what would become the mold of fine dining. Delmonico changed Giovanni to John, his brother Piotrowski became Peter and his nephew Francisco opted to rechristen himself Francois, laying the groundwork for the lingua franca of fine dining to be French, rather than English, and shift away from British food.69 Delmonico’s opened at 23 William Street in 1831, and one of their specialties was raw oysters served on the half-shell. The presentation was luxurious, but oysters were still cheap and seemed plentiful.

During a visit to New York fairly early in his career, Charles Dickens had visited oyster cellars and so they became a bit of an attraction, getting mentions from Henry James in Washington Square and Willa Cather in “Coming Aphrodite.” There were nicer ones and not so nice ones and ones you mostly went to to find sex workers, but it was Thomas Downing who really changed what they could be. Downing had been born to a free Black family in Virginia in 1791, after a traveling preacher had convinced the local plantation owner that being a good Methodist was mutually exclusive with being a slaveowner.70 He worked different jobs around his family’s land, including oystering. He joined the army during the War of 1812, and ended up in Philadelphia where he met and married a women named Rebecca West. They moved to New York in 1819, living at 33 Pell Street.

He worked in the oyster industry, tonging and harvesting and in 1825 he opened the Thomas Downing Oyster House at 5 Broad Street. It was a different experience from the other dives, which were, to the state the obvious, dives. For one thing, women not on the clock were allowed, and as were children, as long as both were accompanied by men. This was a classy place: he wasn’t using cheap oysters as a way to make his money on booze and his costumers were more people looking for a place to spend time with and enjoy their dining companions than a place to spend time with and enjoy their dining companions <wink>. It was spoken of in the same breath as Delmonico’s as a place to go. Some of that was quality: Downing would take a boat out to meet the oystermen coming in from their morning haul and buy the pick of the crop before they pulled in to the market slips. For good measure, Downing would then stick around and bid on oysters to keep the prices profitable for the captains.

They sold oyster preparations you might expect but also oyster pie71 and poached turkey with oysters. Downing sent a sample of pickled oysters to Queen Victoria and she was so enamored she sent him a gold watch. Charles Dickens was a bit snide about it’s popularity at one visit, but Dickins also really thought spontaneous human combustion was a thing so whatever, Dickins. Downing’s Oyster Cellar expanded to 7 Broad Street in 1835 and then also 3 Broad Street, which mean both a larger restaurant and also a larger basement, which was used for both storage and hiding self-emancipated former slaves. He was an active abolitionist and supporter of the African Free School, where his children attended, as well as a co-founder of a committee to protect Black Americans from slave catchers when the Fugitive Slave Law was passed. He sued a trolley company in 1838 when the driver beat him up because he refused to leave, twenty years before Elizabeth Jennings’ suit when they were still segregated. He lived to see the passage of the 1866 Civil Rights Act and the ratification of the 13th Amendment. He died on April 10, 1866, a respected and treasured member of his community, celebrated by his city, loved by his family, and having only had the rights of citizen for the very last day of his life.

Keen-eyed New Yorkers72 will note there is a Downing Street in the West Village but that is not connected, as it seems to have been already been named by 1803, years before Thomas Downing made it to New York. Downing Street is almost certainly named for Sir George Downing and just managed to survive the culling of the very British street names that got American make-overs post-revolution.73 It also could have just been named after Downing Street in London74 but that comes to the same thing. I don’t have anything against Sir George Downing75 but his connection to the city seems to be exclusive to English New York76 and not much to do with the city we’ve been since Evacuation Day, or any service to New Yorkers. It’s written not-quite-in-stone that it’s Downing Street, but why can’t we re-ascribe who we’re honoring with it? And by “we,” I mean the New York City Council.77

But the time has come, to talk of many things: of shoes — and ships — and sealing-wax — of cabbages — and kings — and why the sea is boiling hot78 — and whether pigs have wings. Back to the oysters. Downing’s was respectable enough that women could be there without any risk to their reputation, but they were not permitted in alone. Oysters were just too sexy and too powerful, so ladies-only oyster cellars created a safe space for women to eat oysters, starting with the Ladies’ Fourteenth Street Oyster House opening in 1889 on East 14th off 5th Avenue.79

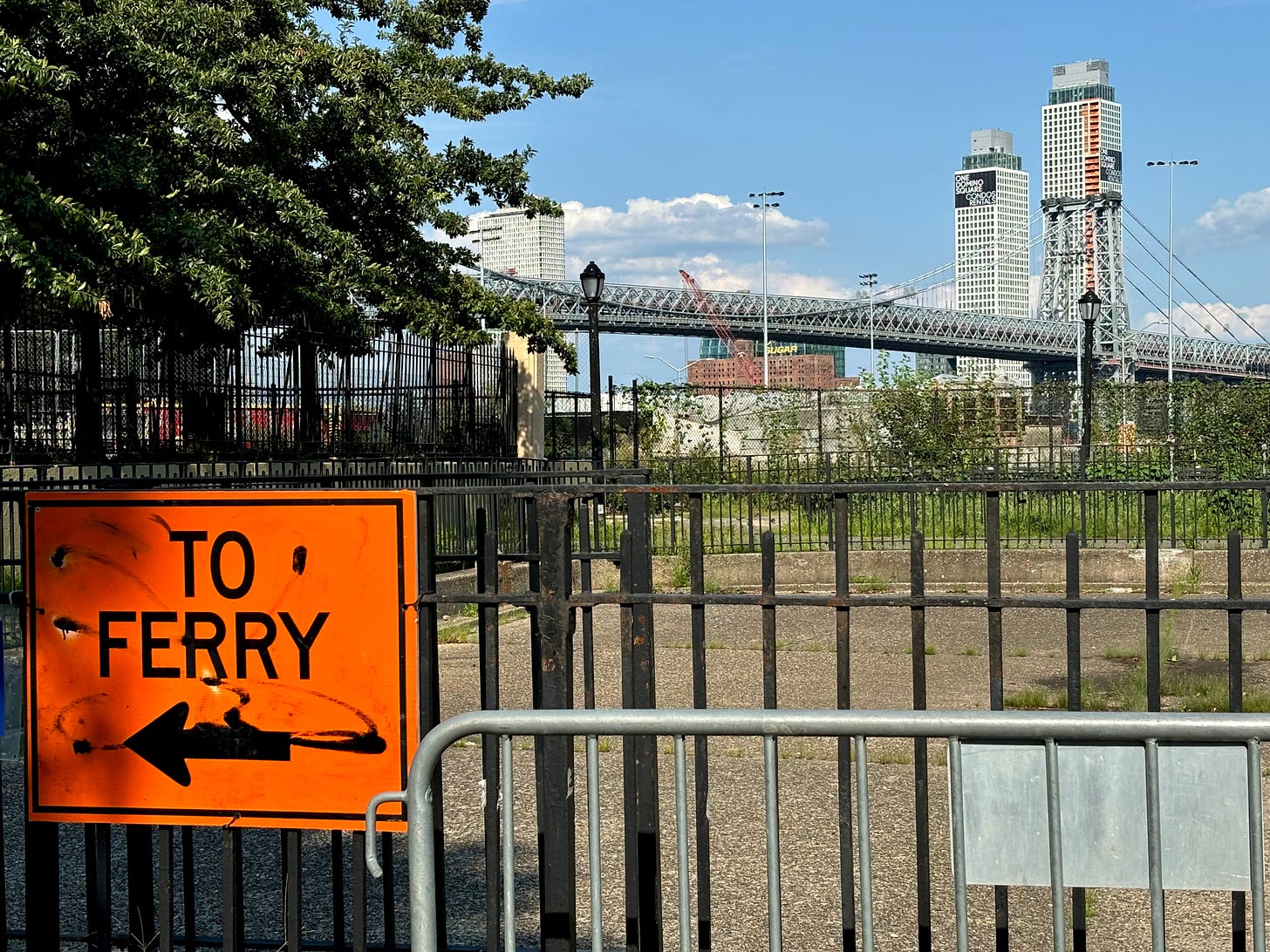

The other people fighting for oyster real estate were the oystermen themselves. Oystering was hugely lucrative as an industry,80 but the prices were low enough that there wasn’t money for waterfront property for a permanent market and since it wasn’t a luxury item, it wasn’t seen as an especially prestigious use of space. Oystermen had started by gathering above Broad Street81 on the East River at Coenties Slip. Many of these were company barges with decorations and second floors with fancy offices, tied off all together, like a floating wholesale market. They got booted up river to Catherine Slip, then to the Hudson and Vesey, then up to Spring then Christopher Street, then back to the East River by the base of the Manhattan Bridge.

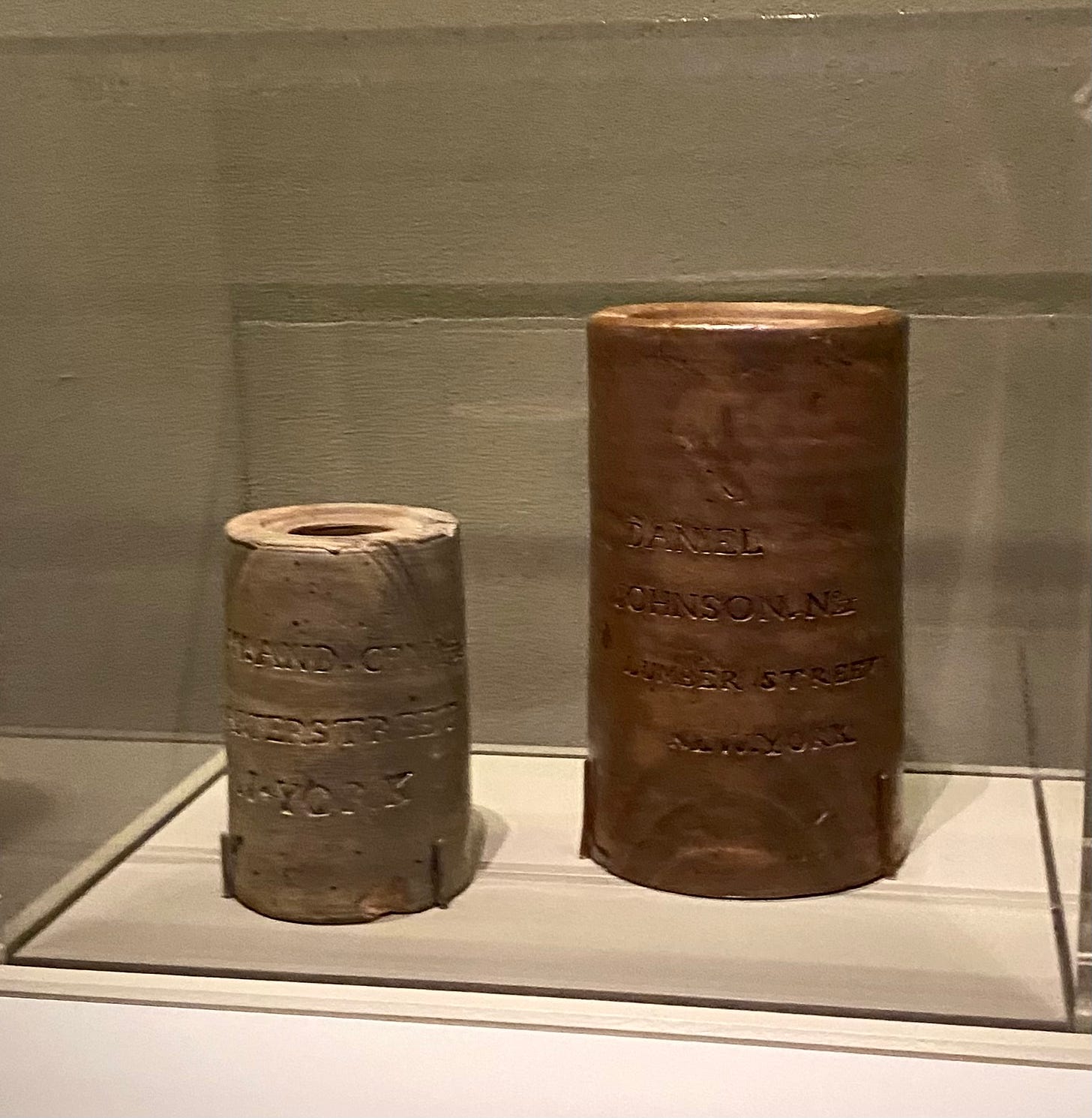

A rising tide lifts all sloops and barges, and the strength of this integrated industry reverberated through the city. One example is noted Black potter, Thomas Commeraw.82 Commeraw was born enslaved in New Jersey around 1771 but the potter who owned his family freed them in his will when he died when Commeraw was seven. He moved to New York by 1795, setting up his own studio in 1797 by Corlears Hook, the area on the Lower East Side Willem Kieft sent troops to wipe out a local tribe.

Commeraw made cooking and food storage vessels with neoclassical embellishments and stamped with his name and studio as an early kind of branding, and did the same for the oystermen who worked on the East River by his studio, making custom oyster pickling jars with the oysterman’s name etched in to make it easy to go back for seconds. He was also active in abolition and mutual aid work, and when the laws in New York state required freemen to have signed affidavits to attest to their legal status, he signed multiple affidavits to help enfranchise as many neighbors as possible.

Another group supporting and supported by the oyster industry were shuckers. Shuckers were seasonal workers in New York and exceptionally skilled. At one speed-shucking contest in Jersey, the winner got $30083 for shucking 500 oysters in 20 minutes and 23 seconds. That backfired a little when people starting thinking shuckers should scale up that pace ten hours a day, six days a week,84 but the average was around 500 – 750 an hour. In 1822, the Fulton Fish Market was set up.85 It was near the ferry, which was good for Brooklyn farmers. It was also open all night – the fruit sellers might close around around 10 PM, but the oyster stalls were always there and it helped solidify New York as the city that never sleeps.

Oysters remained an equalizer across an unequal city, and one of the few times people across class lines were eating the same things, but the problems of the slums were spilling into the oyster beds. In 1863, New York’s slums had a worse death rate than similar neighborhoods in other cities.86 Some of the illnesses were tied to how water was handled, but some of the epidemics were self-perpetuating when contaminated waste was thrown into the same rivers the fisherman were collecting everyone’s dinner from. 1854 saw a bad cholera outbreak and then an oyster panic when people thought that might be the cause.87 The mayor at the time was Fernando Wood, a Copperhead Democrat, who tried to assuage concern by reinstating some of the conservation regulations, like the summer harvest ban. It seemed to settle people’s nerves because 1880 – 1910 was a massive oyster boom, and New York was the epicenter, producing 700 million oysters a year. And a lot of the players we’re talking about aren’t big companies, it’s part time workers and sloop captains and potters and cellar operators. It’s important to underline that this was a vast industry comprised of smaller payment parties. In 1872, New York was a third of the US oyster trade, which was a 25 million dollar a year industry. New York oysters were shipped all over the world, sold in street carts on the Lower East Side, and still the most popular beach food even after the 1867 invention of the hot dog cart designed to sell hot dogs on Coney Island.88 But that’s before the real cost came due. When Mae West said that too much of a good thing was wonderful, that is a great exemplar of the historically significant Little Treat philosophy but not sound environmental conservation policy. As is so often the way when consequences are tossed on a discard plate upside down and regulation sneered at, the Gilded Age Americans went full Dwarves of Moria and dug too greedily and too deep.89 In the “Walrus and the Carpenter,” we are not the wise older oyster, we’re all the walrus.90

Over-harvesting was not the only threat cutting down New York’s once towering oyster population. Cultivation hitched when oysterman stopped using Chesapeake spats during the Civil War. In 1870, oyster beds by Harlem and Hell Gate were abandoned because they were too close to industrial sites and the waste they spit into the water. The Domino Sugar Factory, the Rockefeller refinery and eventually GE poured so many chemicals into the water it was repeatedly made illegal to harvest oysters. By 1880, Jersey oysters from the north shore were no longer edible because of pollution. Sewage still poured into the rivers and trash that was brought out to see on scows washed back into the harbor and onto the beaches. What ended up in the water, be it bacteria or pollution, ended up in the shellfish.91 In 1909, New York hosted the National Association of Shellfish Commissions but they were better at acknowledging the problem than addressing it. New York was producing just over half of what it had a few decades before, and the oysters coming out of the water were starting to taste like gasoline. Sewage shut down the beds in Jamaica Bay in 1915 and again in 1921 and that meant shortages. A 1920 report from the State Conservation Commissioner George Pratt pointed to the rapid decline of oysters and signs that extinction was coming, which in its reporting the Times commented meant that oysters were getting priced out of most families’ reach. Oyster beds were closed but there was no effort to clean up the pollution.92 Industrial waste, pesticides like DDT,93 and radioactive waste from Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island in 1988 all poisoned the water already struggling against a sewage system that released raw sewage into harbor whenever it rained.

The days of the oyster being able to filter the water around the city and feed its inhabits had ended. The oyster that had delighted the Lanape, built communities like Sandy Grove, and fed a whole city was done. Some of the polluted beds were used for seeds to be transplanted to the Pacific, off California and Asia, but oysters are as much a product of their environment as their species, so something lovely has passed from the world.

But the end of the edible oyster of the Hudson is not the end of the story. In 2014, The Billion Oyster Project was born out of The Urban Assembly New York Harbor School, a high school on Governors Island that trains student for all kinds of marine careers: biology, technology, diving, building, vessel operations.94 It started as a school project created by Murray Fisher and Pete Malinowski95 to give kids not only a new way to get to know the history and environment of the city around them but to be engaged in its care. The plan was to cultivate oysters in the waters of New York again, with a goal of one billion by 2035.96 At the rate an adult oyster feeds and filters the water around them, a billion oysters would be cleaning the harbor every three days. And then there’s the other benefits we forgot and then lost in our carelessness: the biodiversity that oysters anchor, that their reefs serve as a protective breakwater so we could lessen damage from storms like Sandy.

It starts with restaurants. Since shells make the best starter reef for spats, Billion Oyster Project collects shells that are 70% or more calcium97 from around 100 restaurants. The restaurants benefit since trash removal is assessed by weight, so what’s taken out to be recycled is money saved.

The shells are brought to Governors Island, where they hang out in a pile for a year98 to be cleaned by sun, rain, bugs and birds. After that, they go in trays for tumbling and washing.

The shells have then been suspended in square cages called gabions in the water, to avoid the industrial chemicals that have settled on the floor while creating a base for new reefs.

The newer idea to offer as a starter reef is a dome made out of eco-concrete99 that spats could attach to and that wouldn’t rust and so risk needing to be replaced. The domes are made by Billion Oyster Project100 and placed by barges in 16 reef sites across the five boroughs.

Oyster Research Stations take the free-floating baby oysters to remote tanks so they can get used to the harbor in safe spaces until they’re spats and ready to attach.101 The reef sites are chosen because the water quality is acceptable, the current isn’t too strong, and there isn’t too much boat traffic but researchers can still get out to the spot to test and monitor. The hope is the eco dome is fully incorporated as the reef outgrows its humble beginnings and thrives, though Billion Oyster Project would go past 2035 to replenish and maintain the new reefs.102

So far, about 122 million oysters have been restored to the harbor though they’re not self-sustaining or reproducing yet.103 Reaching critical mass takes time since the population is really being rebuilt from the ground up.104 There have been some positive signs, though: more whales and seals have been seen in the harbor, and even some seahorses have come back to the Hudson, showing that water quality is on the rise. A wild remnant oyster population is also growing around the Mario Cuomo (née Tappan Zee) Bridge, nesting on shell bags.

We’ve grown further from the water around us than geography suggests: we don’t swim or fish off the city coast the Lenape and other New Yorkers who came before us did, and it’s been decades since Robert Moses slapped a highway in the path to the Hudson, but an oyster can give us a briny taste of what once was. It is, moreover, a creature worth the care in and of itself. Oysters give just by being: their reefs create space for other life and shelter us from the storms, and just their day to day existence filters the water around them and makes the world a little better. They suggest something of kindness and of wonder and the promise of abundance. Our humble Ostreidae Crassostrea virginica are pearls of great price.

The harbor and the rivers are technically full of New Yorkers but sea horses have notoriously low voter turn-out.

And yes, that does sound like a brag but nature did all the work.

Because the water doesn’t care if New York and New Jersey have things to say to each other.

It is on the East side of Manhattan, so that’s on the level, but it’s technically a tidal strait.

Or at least end up next to one another.

Or as Ira Gershwin sometimes pronounced it, “oyster.” I’m sorry. I know that’s a joke about a joke not working when written down but I cannot not make it.

Which is, to be perfectly blunt, a little more history than I can cover today.

That’s a royal we, not me in particular, and only you can evaluate your eye for oysters.

Again, so many years!

This does mean that it’s not actual oysters that make pearls. Pearl oysters are from the family Pteridae not Ostreidae. They’re more closely related to mussels and use a thread to latch onto solid ground rather than a foot. And while we’re No True Scotsman-ing oysters, the irritant that gets covered to form the pearl isn’t usually sand, it’s food that can’t be digested. It’s hard being too classy to make a joke about corn.

Scallops and mussels use threads, if you’re trying to identify a shellfish and are not in a situation where “just ask the waiter” is appropriate.

Oyster toad fish! Black drums! Cusk eels! Snapping shrimp! Sea horses! This healthy reef has everything!

Poop of life. Is that anything?

You can say predators but honestly, some of them are fans. That’s a real potato/potato-oyster/oyster moment. I should call this whole joke off.

Oysters say trans rights, baby!

So dapper!

Ostreidae because they’re oysters!

Oysters can survive almost fresh water and water that’s up to 30% salinity.

The oyster’s answer to Nature v. Nurture is “yes.”

So, New York up through New England and Canada.

And left behind the shell piles to prove it.

And water.

You probably got this from the context but “Lenapehoking” translates to “Homelands of the Lenape.”

Or the “mountaineers.”

In Jersey! Like that bay we were talking about!

Spoiler.

Which was at least 14 European epidemics later, because we’re talking about a genocide so stark that the global temperature dipped down.

And under!

Which means an oyster knife, which did not seem to be a thing, or heat.

Which is why we use “clams” as slang for money. By “we” I mostly mean old-timey gangsters who end statements with “see?” But aren’t we old-timey gangsters with upspeak in a way?

Later Collect Pond, and later than that, poorly filled-in ground.

Woooo, party!

North Brother Island: the forbidden island! The dream!

Or VOC, because I’m definitely not typing Vernenigde Oostindische Compagnie again.

Which I’m just not sure about, my stroopwafel friends: as we have already covered, treats are and have always been important and trout is delicious.

It’s “West” because they did figure out this had nothing to do with Asia.

That’s going to be an ongoing theme.

The Dutch did harvest pearls from Brazil and Asia, which is why a lot of Dutch cities have a Pearl Street: it suggested wealth and prosperity.

Possibly also how co-ops work.

You want a currency based in bamboozlement? I have an NFT of the Brooklyn Bridge to sell you. And frankly, the beads probably had less fecal and cocaine particles than whatever you have in your wallet. No judgement if that’s your thing.

That won’t stick too long: it will eventually be called Bedloe’s Island and is currently Liberty Island.

It’s now known by the name of the man who bought it in 1774: Samuel Ellis.

Also eventually landfill would build out the coast—some deliberately and some just trash filling in space between docks, adding about 60 acres of new coast—so it would no longer be waterfront property.

And even why Americans call cookies “cookies” rather than biscuits: it’s from the Dutch word koeckjes.

Like the white, Protestant kind, not the popular clique meaning.

Which was not really the case in New England, where you were free to worship exactly as the established Purtian power structures dictated.

Which is a bit of a tell in a “This law that says I’m not allowed to hurt and swindle Indians is raising a lot of questions already answered by my law” kind of way.

The wall wouldn’t last that long but the street it stood on kept the name.

This is going to be an ongoing thing.

Including Stuyvesant’s sons.

It was believed oysters harvested in months without an “r” were worse.

In 1770, there were about 500 sex workers in a population of over 21,000, which means about 2.4% of New Yorkers. Maybe oysters really are aphrodisiacs.

Think about it like puttanesca sauce, which you do not have to be in a brothel to enjoy, but some would argue that it doesn’t hurt since that’s where it came from anyway.

About ten shillings at the time, which does not sound as good.

Those are connected points.

Do you ever think that maybe capitalism doesn’t have our best interests at heart?

I get the intention but that’s your loss. Those oysters aren’t going to be around forever. (Spoiler.)

He did not actually invent the steam engine, but he did make it viable.

River change?

A snail that prays on oysters by drilling into their shell and that apparently has no sense of identity beyond that.

Those are the young oysters just about ready to latch on to a nice rock or existing shell, in case you don’t want to scroll back up to where we talked about the life cycle of an oyster.

That’s kind of the problem.

This would also become apparent with the dredges used for cod and flounder, but not until the twentieth century. Oystering was just an early overfishing crisis.

Like “ok for cultivated beds but not wild ones.”

Maybe.

Just to say what may go without saying: the protection was against slavers.

Sandy Ground is still an active community, with some locals whose families go back to the Maryland oystermen who came up to cultivate spats and full citizenship, which sets it apart from similar Black enclaves like Seneca Village in Manhattan and Weeksville in Brooklyn, which is still around but as an amazing museum and community center that you should absolutely visit and tour. SILive.com has done a lovely series on the neighborhood, it’s history and it’s preservation.

It was a point of embarrassment when dignitaries came to town and locals didn’t know where to have a party.

We obviously must not limit our definition of elegant cuisine to European/white countries, but the French do make a nice sauce.

Seems like a given but it was emphatically not!

It was common enough at the time but I don’t think I’ve mentioned it.

Especially my friend Sarah. Hi, Sarah!

He's the namesake of London's Downing Street. Also, Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop was his uncle.

That's probably how Bedford Street in Greenwich Village got his name.

I don’t know all the much about him, which honestly can really help when you’re talking about figures from certain eras.

He helped engender Peter Stuyvesant’s No Good Very Bad Day, marking the end of New Amsterdam and transferring the land of Lenapehoking to the British empire.

Fun fact: Downing Street is located within City Council District 3, which is represented by Erik Bottchner, whose office can be reached at District3@council.nyc.gov and 212-564-7757, if you agree that re-namesaking Downing Street would be a worthy use of a proclaimation.

Climate change.

Oysters were effectively being treated like they had the same pull as Oscar Isaac listening to his women costars at press events, which does not seem accurate to me but maybe we as a society have just gotten sexier, like how the average height has increased?

Worth a million dollars in 1853.

Historically, a pretty oyster-friendly street.

Commeraw, it should be said, was always Black and has been celebrated for his work for centuries but it was only recently that scholarship overcame the negligence and presumptuousness of white supremacy, which had just assumed he was white and then it wasn’t questioned.

About $9,500 today, which is a pretty solid purse!

Which feels like assuming Joey Chestnut eats that many hot dogs all the time.

Eventually giving future New York State Assemblyman and Governor Al Smith his first job.

1 in 36 New Yorker’s who lived in the city’s most neglected neighbors were dying, versus 1 in 44 in Philly and Boston, and 1 in 45 in London and Liverpool.

It’s a bacteria. I checked it for you so I could shield you from descriptions of what the CDC calls “life-threatening watery diarrhea.” You’re welcome.

There’s a non-zero chance Coney Island is called “Coney Island” after the wild rabbits, or conies, that used to have free rein of the place. It could also be named after a guy named Coleman or Dutchman named Cnyn, but c’mon… bunnies!

RIP, Balin. You would have loved goldschlagger.

Goo goo g' booooooooo.

And the fish fish: the sturgeon population dropped and the shad are gone, and what survived was contaminated.

Though a 1934 court case did mean New York was ordered to stop dumping its trash into the sea.

The one that killed Rachel Carson after she warned its effects would bring a Silent Spring. (Killed her because she got cancer from exposure to DDT during her research, not like DDT took her out for revenge.)

So cool, right?

A director and teacher at the school, respectively.

Hence the name. Real good “does what it says on the tin” energy.

Sorry, mussels.

You saw the piles above.

So, shells and rocks.

For only $80, which makes it impressive in its science, engineering and frugality!

Kind of like swimming in a roped off section of a lake, where you’re getting the experience but also shelter.

It takes time for New Yorkers to really become New Yorkers, after all.

Or all surviving.

But not the literal ground, because that’s too polluted for an oyster to be able to build a bed.