It’s easy to take the skyline for granted:1 it is after all, the backdrop to life in the city. It also, in true Walt Whitman-fashion, contains multitudes: it is vast enough to take the place of the horizon but familiar and intimate.2 None of that happened by accident, though the path, like so many of the upper floors of New York skyscrapers, was not a straight line. When we talked about water towers,3 I mentioned the rhythm of old building-new building-water tower, but if the skyline is music then the notes of each building are what make it resonate. How they’re set is a dance between form and function. There are few places that’s better seen than roof tanks, especially when you can’t see them. I won’t re-delve into the mechanics and majesty of water towers4 but one reason people tend to assume they’re relics is you can’t always see them, especially over new buildings, which often camouflage them. But even all dressed up, they’re not going anywhere. But to know how we got here, we need to look back aways.

Let’s rewind to 1856 and 1857, big years for the Big Apple, urban planning-wise. 1856 saw Sir Henry Bessemer develop a process to refine steel that gave builders something wildly thinner than stone and lighter and stronger than iron.5 1857 marked New York City’s first passenger elevator when Haughwout Department Store opened on Broadway and Broome, an important milestone since the attractiveness of height depends on your ability to get up to it.6 The race upwards7 tore through the first two decades of the twentieth century without much pause for breath or safety. Building so high, so fast created a kind of Reverse Mines of Moria, where “the dwarves delved too greedily and too deep.”8 I have mentioned before9 buildings like the Asch Building reached new heights so quickly, the fire department couldn’t keep up, and so when a fire broke out in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory on March 25, 1911, any hope of rescue was 30 feet out of reach. But today is about land use rather than fire safety, so we’ll head a few years later and a bit further downtown to the 1915 opening of the Equitable Building on Broadway and Pine.

That cliffhanger makes it sound like a shocking tragedy is coming but it was more sighs of exhaustion than cries of agony. The Equitable Building was basically the last gasp of these big "Brutalism But Make It Fashion" blunt towers blocking out the sun before we collectively looked up from the dim sidewalk and said "Nah. This sucks." You know what that means? It’s rezoning time, baby!10

Like all successes, the 1916 Zoning Resolution has many fathers,11 but because this is a zoning resolution, their names are not shouted in celebration the way they should be. So what was it? “A Resolution regulating and limiting the height and bulk of buildings hereafter erected and regulating and determining the area of yards, courts and other open spaces, and regulating and restricting the location of trades and industries and the location of buildings designed for specified uses and establishing the boundaries of districts for the said purposes.”12 In practice, this meant progressive setbacks. But not the kind the Supreme Court has been enacting: the good kind.13 Progressive setbacks mean the way buildings are stepped inward as they reach certain heights. Think about looking straight down a street, with buildings rising on either side. Now imagine a V, with the point in the center of the street. The ratio of the ascending sides determined how high and far out any given building can be to still allow light to reach the sidewalks and air to move about in the way one expects. This is where I realized that I owe an apology to my 10th grade math teacher because I was pretty sure geometry was never going to intersect with my interests14 but here we are: sorry, Ms. Edgar.15 The acuity of the angle would be determined by different factors, like the neighborhood and how residential or commercial it was and the width of the street. What does that look like?

There’s no more iconic example of step backs or hidden water towers than this. Not to sound basic, but the Empire State Building is an extremely beautiful example of setbacks and their benefit: the footprint is wide but it’s height doesn’t begin at its perimeter so there’s no sense of looming menace for those on the street below.16 Also notable in its design is that the water tanks are housed within the building rather than on the roof.17 That choice—and we’ll be going over different iterations and what it can look like while we talked about the people who made setbacks a step forward—was also a mix of aesthetics and practicality, as dispersing the water towers throughout an especially large building can distribute both the pumping system to get water up and the reservoir to supply water down as needed. For the record: though its roof was kept free for the possible mooring of dirigibles and other airships that never ended up being feasible, there are ten water tanks within Empire State.

So who is responsible for our city taking two steps forward by ensuring our buildings took progressive steps back?18 The man who walked away with the nickname “The Father of American Zoning” was Edward Murray Basset. Basset was a lawyer from Brooklyn19 who’d served a term in the House of Representatives20 but didn’t run for reelection as he was more interested in serving at a local level.21 He worked on tax law and tariffs and the growth of the subway, but he enters our story because chaired the Heights of Buildings Commission for the Board of Estimate,22 which put forward the recommendations that became the 1916 Zoning Resolution. He would go on to man multiple zoning and planning commissions in the city, then the state and then the National Conference on City Planning under Herbert Hoover when he was Commerce Secretary. Despite the nickname however, Basset didn’t do this alone: no man is an island.23

Now, I know you’re champing at the bit for more details on the Heights of Buildings Commission, so let’s get into it. The driving force behind it was George McAneny. McAneny was born in Jersey City in 1869 and went to work at Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World after school. He spent the next half century racking up an impressive assortment of civil service and journalism positions, often bouncing between the two: Manhattan Borough President, executive manager of the New York Times, chairman of the transit committee on the Board of Estimate where he worked with Edward Basset, Alderman (and president!), and Comptroller.24 He’d been pushing for regulation since before Equitable Building went up, citing the need to “to arrest the seriously increasing evil of the shutting off of light and air from other buildings and from the public streets, to prevent unwholesome and dangerous congestion both in living conditions and in street and transit traffic, and to reduce the hazards of fire and peril to life.” Which is all pretty hard to argue with.

I’ve now mentioned two people responsible for this zoning resolution and I bet eagle-eyed readers noticed neither of them have any training in architecture or engineering. Enter George Burdett Ford, the (one particular kind of) brains of the operation. Ford was born in Massachusetts in 1879, and trained at Harvard, MIT and then Ecole des Beaux Arts in France. While working at an architectural firm in the city, he co-founded the Technical Advisory Corporation of New York, an urban planning and environmental consulting firm, and that was how he came to the Board of Estimate’s Heights of Buildings Commission in the wake of the Equitable Building’s poor reception. It was his V formula that I described earlier and his architectural sensibility that re-shaped the grid in 3D, setting the tone for what New York would look like for the next 50 years, and by extension the rest of the world. Because New York led the way up, and other cities followed the example of how we built and how we climbed, even if they didn’t formally set the regulations we did.25 After World War I, he served on the commission to help restore Reims, France and, on his return to the states, he advised dozens and dozens of cities implementing urban planning initiatives and served as a consultant for the New York Regional Plan with funding from the Russell Sage Foundation.26 I think it’s worth underlining that the leaders behind this commission were two politicians without an eye towards higher office and an architect known for rebuilding and as much as building: this was not legislation meant to be flashy, this was work meant to be invisible but deeply felt.

So that’s who made the rules but who made them look good? One was Emery Roth, who designed the buildings above. Born Imre Roth in 1871 in Gálszécs, Hungary,27 his family emigrated to the midwest when he was 13. He met and impressed Richard Morris Hunt, who we last saw sniping at Olmsted and Vaux about Central Park being unfit for anything but sheep, at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition28 who recruited him and brought him back to his office New York.

Another was Rosario Candela. Candela was born in Palermo, Sicily in 189029 and emigrated to New York in 1909, with very little in the way of money or English. By 1915, though, he’d graduated from Columbia’s School of Architecture. A lot of his first gigs came from other, more established Italian immigrants, but it didn’t take him long to catch on. He became a big of part of moving the very rich from mansions into luxury apartments, designing duplexes and triplexes with everything a leader of high society could want for entertaining, from high ceilings to gracious dining rooms, to maid’s rooms. He took a puzzle box approach to setbacks, creating beautiful terraces where everything felt a bit special and unique. For much of the 1920s, his name had the kind of sparkling draw that Sanford White’s had had during the Gilded Age, but without any statutory rape allegations,30 and his work came to epitomize luxury design. Roth and Candela together used the necessities of the 1916 regulations to redefine the architecture of the city, and everyone who took their cues from what New York did. As part of that balance of form and function, each tended to hide the building’s water towers in structures that matched the aesthetics of their design.

The only problem was that once the Great Depression set in, there was limited call for luxury triplexes. He designed a few buildings aimed at middle-class residents during the 1930s but eventually set his puzzle box skills to cryptography, joining coding efforts during World War II and later teaching it at Hunter College.31

So we arrive at 1961 and the new zoning regulations coming into effect, appropriately named The 1961 Zoning Resolution.32 This resolution replaced Ford’s “V” with the Floor Area Ratio (or FAR), which determined height based on the footprint of the building. It also built in parking requirements because we’re talking about a period when giving preference to cars over people was all the rage.33 The twin muses often cited for what rezoning hoped to encourage more of are the Seagram Building on Park and 52nd and Stuy Town. The problem with Stuy Town as a model was that it was segregated, and it took years of lawsuits for Black tenants to be able to rent and not just sublet an apartment.

The Seagram Building seemed an ideal example of urban planner Le Corbusier’s Tower in a Park model.34 “Park,” however, didn’t mean public land: with the new zoning laws and the Seagram Building as template, the city created POPS: Privately Owned Public Space. If a developer wanted to build higher than the allotted ratio would allow, they could trade for extra height by creating accessible space within their footprint for the public to use and enjoy. I love a good plaza but there’s not a knife in the world sharp enough to cut the tension inherent in the phrase “privately owned public space.”

Anyhow, let us return briefly to pointing up at the sky and saying, “Oh look, a water tower!”

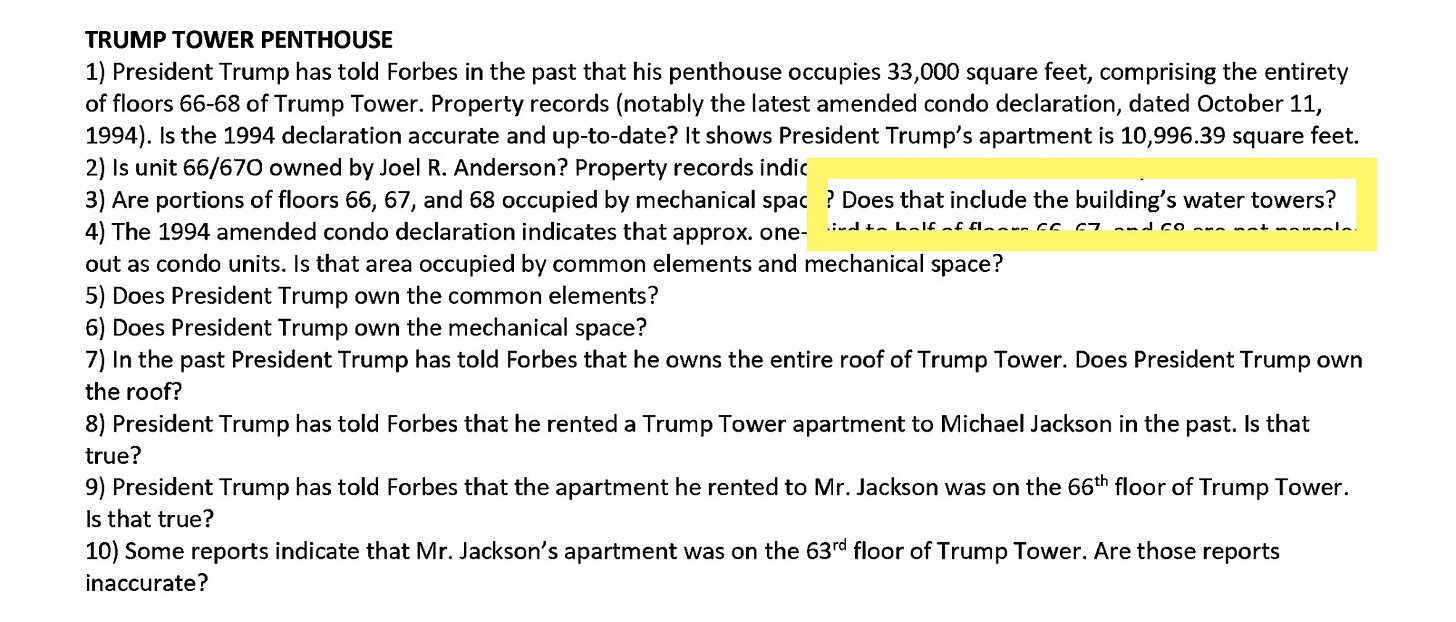

The question of water towers and where and how they’re housed can sound like arcana but it can have very real consequences, creating pressure that has nothing to do with how forcefully the water comes out of your tap. In the recent civil suit brought by New York Attorney General Leticia James against Donald Trump and other executives of the Trump Organization for lying about his wealth, one of the assets in question was the size of the triplex in Trump Tower. How does an innocent water tank get roped into the graft?35 By potentially getting included in the square footage. Wanna see a slice of Exhibit 72? It’s from an email from a Forbes reporter checking facts on assets with Trump Organization execs.

Democracy may die in darkness, but it needs water to thrive. Perhaps the lesson we can learn from the skyline itself is that everything will be brought into the light and that even the concealed water towers get cleaned once a year.

If you live here. Visitors seem to enjoy it!

And literal multitudes, since a lot people are here every day.

In newsletter form, I mean. I talk about water towers a lot.

BUT IF THAT’S SOMETHING YOU LIKE TALKING ABOUT, YOU KNOW WHERE TO FIND ME.

Other people were independently working on the same idea, but since it ended up being called the Bessemer Process, he gets the shout out for the moment.

Even in this housing market, you don’t hear much about twelve-story walk-ups. Oh god, I’ve just given the real estate lobby ideas, haven’t I?

Ever upwards, even!

I did actually push up my glasses immediately after typing that, if you were wondering.

And will again! There’s no cocktail party I won’t plunge into grim silence by recounting historic tragedies!

Pwa pwa pwa pwaaaaaaaa!

And at least one mother.

Is it hot in here or did someone just regulate the height and breadth of buildings by neighborhood usage?

Ha ha. Ha ha. Ow, my rights.

See what I did there?

Also, I hope you never took my homework as a comment on your teaching.

There’s a further marriage of art and necessity as its design is also rooted in a desire to be taller than Chrysler Building.

Et tu, (ES)Brute?

These are just going to keep going.

Born in 1863, so just a few years after the first passenger elevator and the Bessemer process for refining steel.

He represented New York’s 5th District, which is now in Queens.

A hero for that alone, honestly.

And the Board of Estimate had only been established by amendment to the city charter in 1901, so it was still pretty shiny and new.

Four boroughs are, but don’t worry about it.

During his time as Borough President, he’d helped restore City Hall with funding donated by philanthropist Olivia Sage but just put that in your pocket for now.

That’s a real hair flip/nail check of civic pride moment.

That’s Olivia Sage again! She was born Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage, and does not seem to be related to the General (the Tammany man, the ship, or the disaster). Her husband Russell Sage died in 1907 and left her millions to use and give away she pleased, and one of her causes was the Russell Sage Foundation, which sought to find actionable solutions to civil issues. She had very strong opinions on the need for and role of women in the public sphere (and Bridge Whist), some of which involved metaphors about weeds of vice strangling flowers of femininity but some of which were quite blunt assertions that wealthy women had a duty to make themselves useful and that “blue blood” in America didn’t come with or from cash.

If you think Imre to Emery is a change, Gálszécs is now Sečovce, Slovakia. The other fact I learned about Gálszécs is that the Jewish population in 1940 was 1,026 and the Jewish population in 1948 was 98. Roth’s family had left long before, but the rest didn’t.

Of The Devil in the White City fame.

This would make him approximately 15 years older than Sophia Petrillo if that helps you “picture it.”

It’s a low bar but a crucial one!

Which, as second careers go, is extremely cool.

Keep in mind: this will not affect water towers and their need, just the buildings they’re on top of.

I blame Robert Moses. I mean, for a lot of things, but especially for how much he bent the city around cars.

I’d explain but it really does what it says on the tin, you know?

I’d like to make a “padding his pad” joke but honestly, the moment may be too venal for puns, and that apartment too tacky.