It is a truism of American history that Massachusetts is the birthplace of the American Revolution1 but it is equally true that the revolution only survived because Brooklyn kept it alive. In the pantheon of History We All Agree Is Very Important,2 however, the Battle of Brooklyn3 doesn’t really get its due. Maybe because we’re not a nation that processes defeat well.4 Maybe because we’re not a nation that accepts New York as uniquely and ideally American. But the simple facts are that the largest battle of the revolution was fought across the streets and parks of Brooklyn, that we lost quite unequivocally, and that the reason we lost the battle but not war is the ingenuity and courage of those in Brooklyn in the dying days of August, 1776. America as a democratic republic and New York as a city are built on the blood spilled and the bodies that fell without marker,5 one more literally than the other. Wanna see where the bodies are buried?

Technically, our story begins about 18,000 years ago when the Laurentide Ice Sheet tore through the rocks of what’s now King’s County as the melting glaciers of the waning ice age redrew the earth itself, with new stone arcing over the land at the edge of the ocean. The retreating6 glaciers left ridges and hills so tall, they towered over the rest of the land mass that would become Long Island. For expediency’s sake ,7 after that exciting thaw, we’ll skip ahead to 1775 but the topography matters, since when we talk about fighting for the high ground, that’s not a metaphor.

A lot of scrapping and violence and questions of the issue of taxation without representation paved the way,8 but the fight for independence began recognizably in April of 1775 with the battles of Concord and Lexington in Massachusetts and the beginning of the Siege of Boston. By June, the British led by William Howe seized Bunker Hill, winning land but losing more soldiers than the American forces did and learning to be cautious despite the assumption that the Continental forces were inexperienced and smelly.9 Bunker Hill was followed by several months of stalemate and reinforcement and waiting and waiting and waiting until the British evacuated Boston in March of 1776. That Howe would set his sights on New York after the Siege of Boston seemed pretty inevitable. For all the same reasons the English had first moved to take New Amsterdam from the Dutch and the Dutch had stolen the Lenapehoking from the Lenape – especially the bay—but now with the added bonus that apparently the English army did not particularly enjoy attempting to occupy Puritan New England and very much wanted to set their headquarters somewhere a little more fun.10

The Brooklyn all the generals are eying is over a century from being part of New York City11 and comprised of six towns: Breuckelen,12 Nieuw Amersfoort which pretty quickly became Flatlands,13 New Utrecht,14 Boswyck or “little town in the woods” which anglicized into Bushwick,15 Midwout which would become Flatbush16 in short order, and Gravesend.17 Gravesend is notable because it was founded by an Englishwoman even though it was part of Dutch New Amsterdam18 and that’s going to be significant later.19 Breuckelen20 would eventually soften into Brooklyn,21 and that town started to swallow up its neighbors like Pacman gobbling little dots, and that’s the village where Washington was based. There were four main arteries through these six villages and the rocks and ridges that curved around them: Jamaica Pass, which ran west from East New York into Brooklyn, Flatbush Pass, which ran south-west through the village of Flatbush eventually roughly lining up with what’s now the East Drive in Prospect Park,22 Bedford Pass, which sounds like it should be a forerunner of Bedford Avenue but ran through the village of Bedford,23 and Gowanus Path, which ran along the canal and into what’s now Third Avenue, which divides the forts built along Brooklyn Heights and Prospect Park, which is going to matter.

Washington, like many celebrities looking to keep things low-key, set up headquarters in Brooklyn Heights. Cornell House, or Four Chimneys,24 stood at the water’s edge, in Brooklyn overlooking Manhattan, across the street from the apartment where W.H. Auden lived on Montague in the first years of World War II25 and just a few doors past where Arthur Miller lived with his first wife not long after Auden had moved out.26

The thing that’s going to get very important very quickly is knowing Howe will hit New York is not the same as knowing where in New York Howe will hit.27 The Continental Army was limited and now had to cover a wide swath of land and sea. Washington had received some intel28 that Howe would strike if not at Manhattan, then by the East River, so he had forts manned on both coasts across both cities as well as Governors Island.29 Hindsight means that we know the exact amount of time between the Siege of Boston and the Battle of Brooklyn and no one else did30 but it would have been assumed they had some lead time to prep, and the Continentals spent those months on forts. Israel Putnam, a Connecticut farmer turned militiaman31 led the effort to establish the fortified points along the defense line. This included building and arming Fort Greene on what’s now Fort Greene Park,32 Fort Putnam,33 on the hilly terrain to the east, Fort Stirling named for the American general with the very British-sounding name, William “Lord Stirling” Alexander,34 also off what’s now the Brooklyn Heights Promenade,35 Fort Defiance,36 the furthest west of the Brooklyn Heights line, out by Red Hook.

Putnam also beefed up Fort George in the Battery,37 where the Custom House named after then-Artillery Captain Alexander Hamilton38 currently stands, and Fort Ring and Fork Corkscrew,39 as well as adding artillery to Governors Island.

If you’re following along with a map, you may have caught there were some towns and passes I mentioned initially that don’t seem to have added defenses and be saying, “Magin-uh oh.” The area around East New York and Jamaica Pass was vulnerable and there gaps in fortifications around what the Lenape knew as Guana and we call Gowanus.40 And Howe knew it because he got word from Gravesend, a bit of a Loyalist hot spot since they’d been English so much longer than the rest of the city. When Cornwallis sailed up from South Carolina, he made port in Staten Island and on August 22nd, 1776 found soft landing at Gravesend Bay.41

And what exactly were all those forts up against? A lot. By August, the British forces included 420 ships42 carrying over 34,000 soldiers,43 which was more than the population of the city at the time. It was the largest expeditionary force that had or would be assembled for centuries. People described the ships crowding the rivers and harbor as if all of London were afloat, and with the ships so crowded you could walk across the East River without getting your feet wet, and the sky so thick with masts that it appeared to be a swaying forest. And here is the time to say the Continental army might never have been able to hold New York. Noted Massachusettsian44 John Adams described the city as “a kind of key to the whole continent.” And it is a series of islands45 against the British Navy, which was the main reason there was a British empire.46 The Continental army in New York was around 10,000, with about ¼ out of commission from illness or bad health from poor water and conditions at any given time, which is, mathematically speaking, less than 34,000.47 Which is all to say even if the American fornications had been flawless, there’s no knowing if the Americans could have held New York. But the fortifications weren’t flawless. There was a gap in East New York and Howe pried it open with the barrel of a gun.

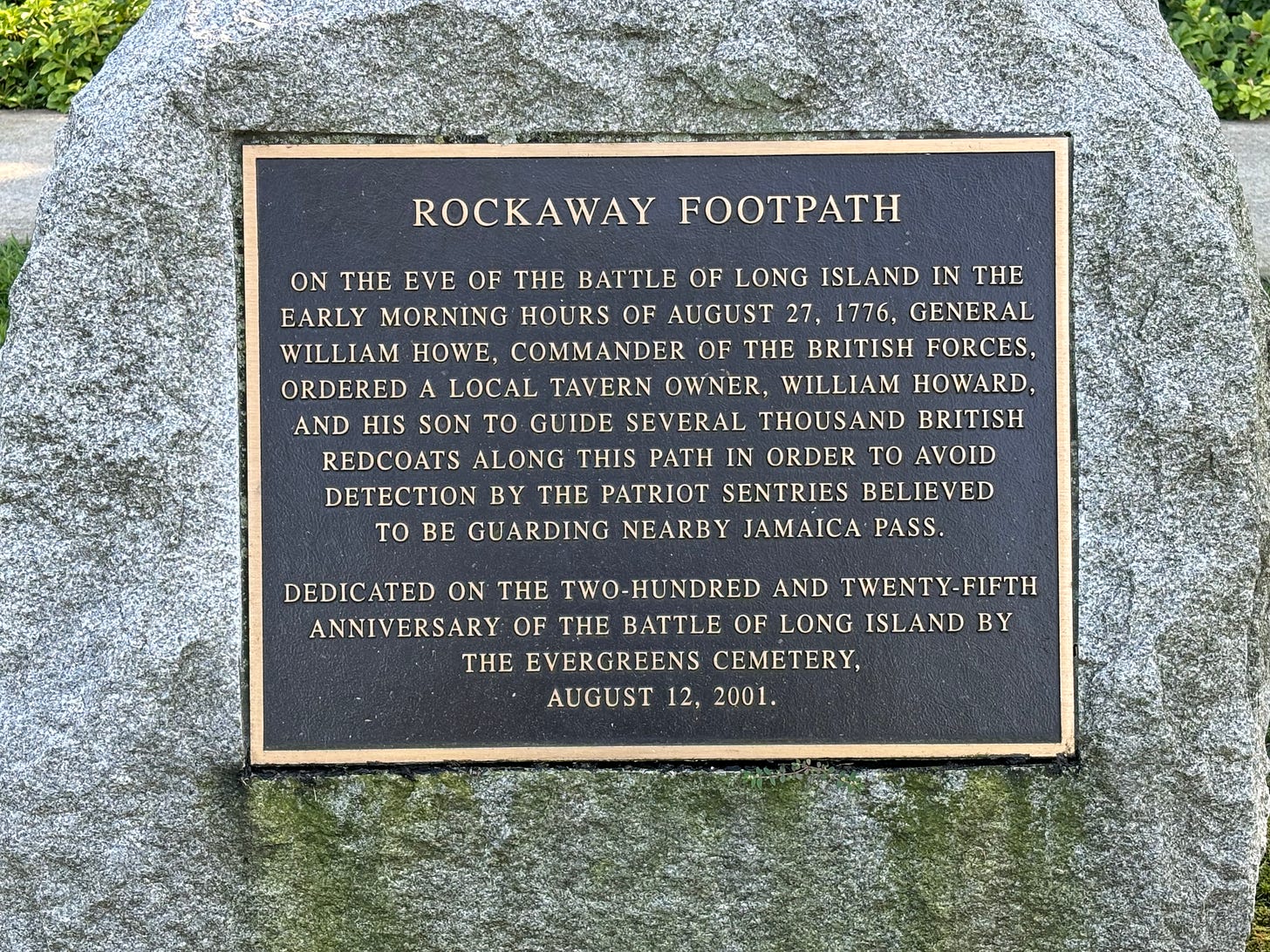

Howard’s Tavern or Howard’s Half-Way House was run by William Howard at the edge of his farmland, called Howard’s Wood48 at the corner of Broadway and Jamaica. Howard was awakened in the wee small hours of August 26th by three men. It’s not the wildest thing for an inn keeper to have to keep hours with travelers, but his “guests” turned out to be Generals Howe, Cornwallis and Clinton,49 requesting to be led through the American lines and past their defenses. Howard declined—he was not from Gravesend and not on the English’s side—so Howe asked again, this time at gun point.50 And so the Howards,51 Howe, Cornwallis, Clinton, and about sixteen thousand red coats made their way from Jamaica Pass through the Rockaway Footpath, bypassing Putnam’s defensive ring, which was more of a defensive horseshoe, which is not, in fact, A Thing.

Howard’s Tavern survived the war and the beginnings of the United States, with stories that he’d not only survived a run-in with our fearsome foe but had even secretly sent a servant to warn Washington the British were coming (from the east) helping bolster his celebrity. It was sold in 1867. In 1859, though, the city was growing and a warehouse to hold trolley cars for the Broadway Railroad’s streetcars had opened on the corner. They shifted to buses in 1931 and were taken over by the city in 1940 as the city started consolidated transit under the auspices of what would become the MTA. By 1956, streetcars had gone the way of British rule in the states and the current building, the East New York Bus and Garage Transportation Building was open.

In fairness to Washington’s planning,52 Jamaica Pass wasn’t unguarded, it was just very, very lightly guarded: General Sullivan had assigned five men to watch the pass, including Robert Troup, a former roommate of Hamilton’s, among others. The British knew they were being scouted and kept campfires lit far to the south of main battalions to disguise their location. When the campfires weren’t enough to keep their location under wraps, the guards were captured.53

The British picked their way west through a wooded area that’s now Evergreens Cemetery, which extends over the border of Brooklyn and Queens and would have taken the British into the village of Bushwick. This section of the Woody Heights would be incorporated as a rural cemetery The Evergreens in 1849.54 It’s part of Cemetery’s Row that cuts across Brooklyn and Queens and has over half a million New Yorkers in residence.55

Things kicked off in earnest before sunrise on Tuesday, August 27th. British General Grant56 had taken a westerly path, marching his men along the coast from Gravesend Bay and up to a farm road called Martense Lane. Some of Grant’s scouts found a watermelon patch in the garden of the Red Lion Inn by what’s now the 4th Avenue edge of Green-Wood and tried to help themselves.57 The Americans fired on and the battle was begun. By 7 AM, Stirling moved forward from the Old Stone House with 2000 men from a Delaware militia to block Grant’s progress at Martense Lane and Shore Road58 by Bedford Pass.

By 9 AM, Stirling heard the British set off a signal cannon and it was coming from behind his line: they had been distracted by a violent kind of sleight of hand and were surrounded.59 He started to fall back to Bedford along the ridge with his line forming from west to east along what’s now 20th Street. This kept the high ground now commemorated as Battle Hill60 on his left flank to shield his men from Cornwallis’ troops as he led the way back to the forts lining Brooklyn Heights that represented months of labor and preparation overseen by General Putnam and that would not slow the British.

The retreat had the advantage not only of topography but Pennsylvania sharpshooters lining the ridge, who could be accurate up to 300 yards.

Stirling sent 300 men, largely from Huntington’s 17th Connecticut Regiment, led by General Samuel H. Parsons61 to take Battle Hill. They would end up inflicting 1/3 of Britain’s casualties from the whole of the battle as they held the hill, long enough for the rest of the army to retreat and regroup. Stirling had retreated without sending them notice, however, and when they realized their comrades were safe62 and they had done what could and should, many surrendered and 200 men were captured trying to rejoin their lines.63 Most of them would die in British prison ships. Cornwallis would later say the Americans “fought like wolves.”

The wooded land around the high ridge became New York’s first rural style cemetery, Green-Wood, in 1838, and effectively Brooklyn’s first public park. After the addition of a ferry service for easy travel64 and permanent residents who captured the public attention,65 Green-Wood became so popular with the living that only Niagara Falls had more visitors and so popular with the dead that burials increased exponentially, expanding its acreage throughout the nineteenth century. In 1862, they offered free internments for Union soldiers.66 It’s also a Level 4 arboretum. It’s open to the public and offers historical tours, bird watching, informative pointing at different trees, concerts and performances, and takes its responsibility as the keeper of its residents’ stories quite seriously. There’s also a great taco place across the street from the 5th Avenue entrance.

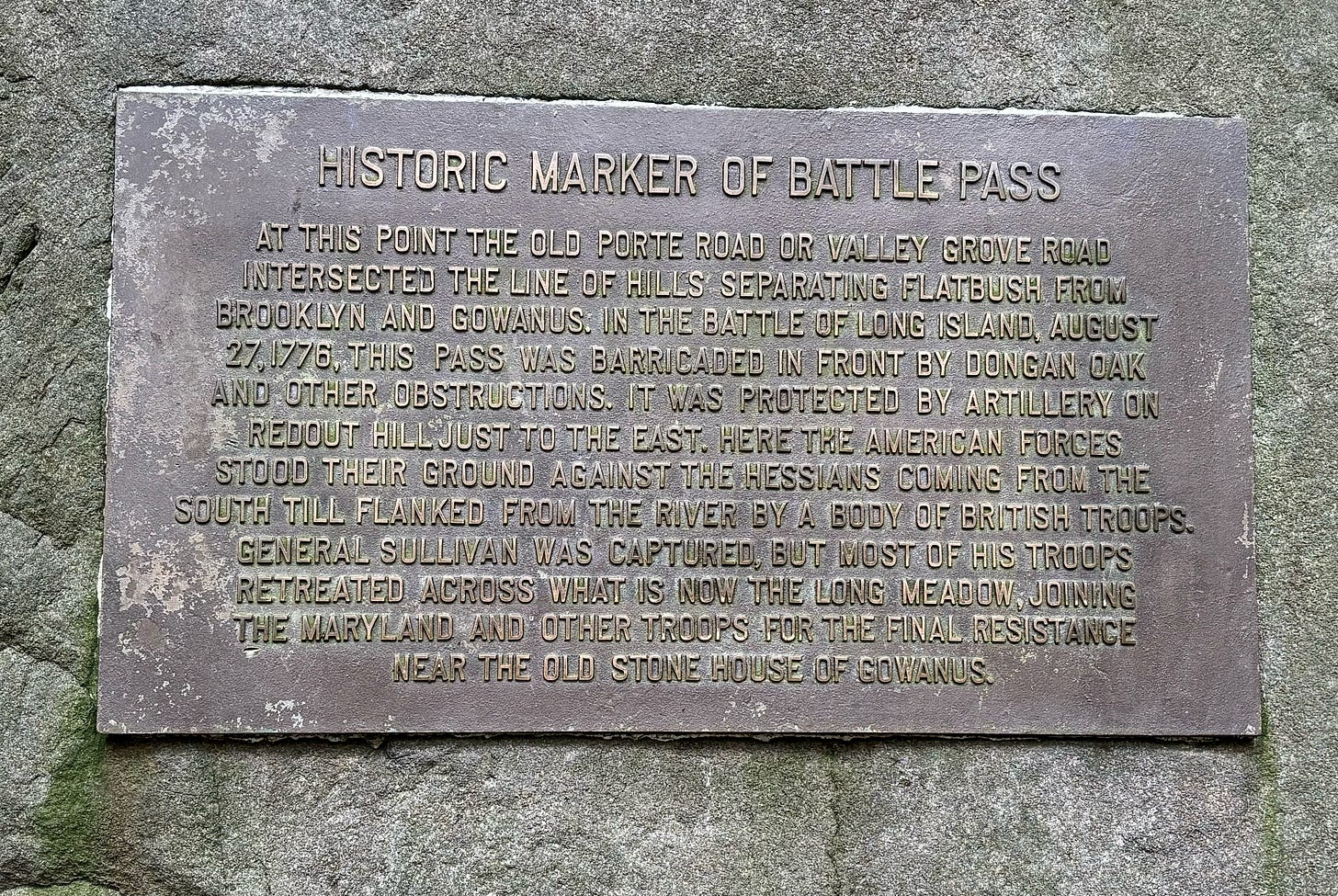

Let’s look a little north and east towards Flatbush Pass. As we’ve seen, the Americans expected the British to take any path other than Jamaica Pass.67 The Americans, led by General John Sullivan,68 had felled trees, including a white oak that been an unofficial border between Brooklyn and Flatbush69 to create an armed blockade that could hold back the British.

While Grant distracted the Americans under General Stirling on Battle Hill, Hessian troops under Leopold Philip de Heister70 and eventually British soldiers under General Henry Clinton71 met the blockade along what is slightly ominously known as Battle Pass without engaging. Until the signal came at 9 AM.

When the cannon shot that burst Stirling’s hopes of victory by revealing how entrenched the British already were went off, the British forces attacked: De Heister’s Hessians at the front and Clinton and his men from the rear. The Americans could not retreat and could not overcome an enemy that vastly outnumbered and outmaneuvered them and were slaughtered in Prospect Park. Sullivan ordered anyone who could to fall back to Brooklyn Heights. Sullivan himself charged the Hessians with pistols in each hand until he was captured.72

In the mid-nineteenth century, Brooklyn saw the success of Central Park one city over and decided to match it, if not surpass it. City planners eyed the woods that had become familiar to Von Heister und Co, envisioning a park that encompassed Mount Prospect, Brooklyn’s second highest point,73 at Eastern Parkway and Flatbush Ave. That got nixed by Calvert Vaux74 after he surveyed the ground in 1866 and redrew the plans. Olmsted and Vaux were appointed chief architects in 1866 and worked straight through 1873, when the park wasn’t so much finished as out of money and so, like a Goonie, declared good enough. As work was underway, they found remains of the soldiers killed along Flatbush Pass in the Battle of Brooklyn.75 The park would be expanded thought 1890s,76 when the City Beautiful movement made that kind of project morally as well as aesthetically pleasing, and all through the twentieth century.

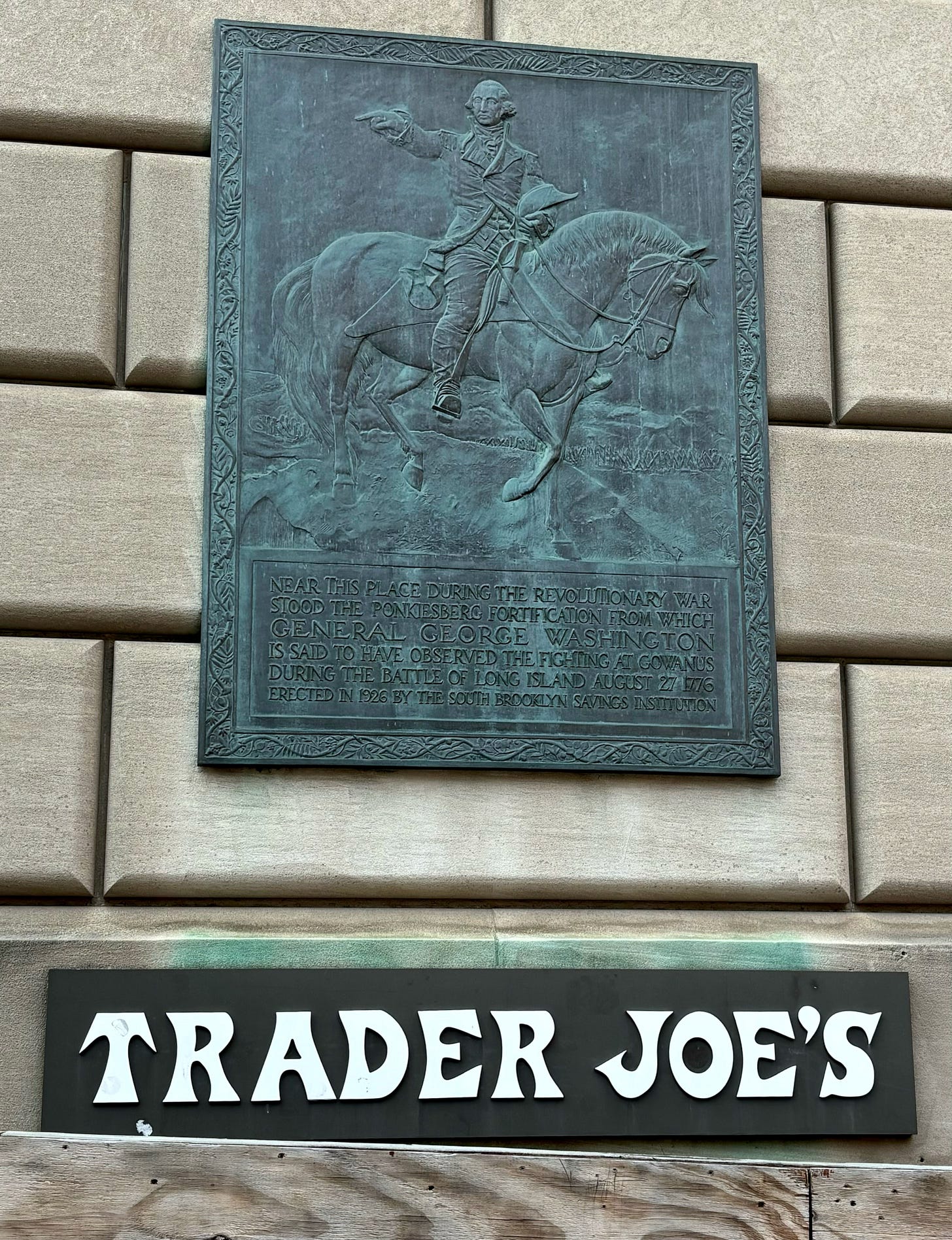

Eventually, there would be a war council held at the Cornell House but Washington spent a good part of August 27th tracking the battle from the Ponkiesberg Fortification in what’s now Cobble Hill,77 around Atlantic Avenue and Court Street. It was here, supposedly regarding the soldiers from Major Mordecai Gist’s Maryland regiment that he mournfully noted, “what brave men I must lose this day.” Other less skilled and sacrificing soldiers got a more irritated, “Are these the men with which I am to defend America?” and “Good God, have I got such troops as these?” There was also a fair amount of swearing and storming around from Washington, but to be fair: the day wasn’t going well.

The building that stands there now was built in 1924 for the South Brooklyn Savings Institution, which had been founded in 1850 and had been moving around the neighborhood to larger and grander buildings until this was commissioned in 1919. The plaque went up in 1926. It would change its name to the Independence Savings Bank78 in 1930 and then sold to Sovereign Bank in 2006. The Trader Joe’s opened in 2008.

The Marylanders Washington spoke of were at the Vetche/Cortelyou House, or the Old Stone House. The Old Stone House had been originally built by Dutch immigrants79 in 1699 on what’s now Third Street between 4th and 5th Avenues and what was then still the village of Brooklyn. It changed hands through the day, but by the afternoon the Continentals were trying to protect Stirling’s retreat as Cornwallis targeted the Old Stone House to stop them. Stirling ordered his men west over/into the Gowanus Creek, which used to run quite close to the Old Stone House,80 leaving the best trained soldiers to cover the rear guard: Smallwood’s Maryland Regiment under General Mordecai Gist81 who would be known as the Maryland 400. Quite reasonably, that was because there were 400 of them, against approximately 2000 Hessian and Scot soldiers but the nickname does have a kind The 300 Spartans ring to it. It was, if not an outright suicide play, very clearly a knowing sacrifice to allow the rest of the army to escape the British forces that had been encircling them in a tighter and tighter net since the night before. Gist broke through with just over a third of his men. That left over 250 Marylanders unaccounted for. Some could have escaped, though that seems unlikely in its optimism. They could have been captured, which meant the British prison ships which was often its own death sentence.82 Or they’re buried somewhere in Brooklyn still. What we do know for certain is they marched into the enemy for Washington and for their comrades. The afternoon was described by Walt Whitman’s aging veteran in “The Centenarian’s Story” like so:

I tell not now the whole of the battle,

But one brigade early in the forenoon order'd forward to engage the red-coats,

Of that brigade I tell, and how steadily it march'd,

And how long and well it stood confronting death.Who do you think that was marching steadily sternly confronting death?

It was the brigade of the youngest men, two thousand strong,

Rais'd in Virginia and Maryland, and most of them known personally to the General.

The Vechte family held the house after the war, selling to Jacques Cortelyou in 1797, whose son’s family lived there through 1852, as the creek was filled in and row houses came to define the neighborhood and the Cortelyous sold to Edwin Litchfield, a railroad developer who would sell a lot of the land to the city that’s now Prospect Park. The block around the house became Washington Park in 1883, and the house served as a club house for the Brooklyn Dodgers when they practiced at the Washington Athletic Field.83

The house burned down in 1897 but was recreated as a comfort station for the park by Robert Moses,84 and it’s now also a museum and community center. When it opened in 1935, The Brooklyn Eagle described the significance of the place with a quotation: “the Declaration of Independence was sealed in blood on the fields of South Brooklyn.” The bodies of the Maryland fighters have never been found.

Some people think the Marylanders are buried under what was Jacob Van Brunt Martense’s farm, whose lane Grant used to meet the Americans in Green-Wood, but the closer suggestion is under the Michael A. Rawley85 American Legion at 3rd Avenue and 9th Street. It is something between a best guess and, considered it’s being marked by the American Legion, the most appropriate option, but people do look for the 256 bodies whenever there’s new building and they haven’t been found. The American Legion, just to be thorough, is a veteran’s organization established just after World War I open to anyone who has served in any of the armed forces. 193 9th Street was built in 1931 and the American Legion seems to have been there for a solid 60 years and they always commemorate August 27th, 1776.

As the veteran in Walt Whitman’s “The Centenarian’s Story” sighs:

Ah, hills and slopes of Brooklyn! I perceive you are more valuable than your owners supposed;

In the midst of you stands an encampment very old,

Stands forever the camp of that dead brigade.

Some of the Continentals from Prospect Park had been able to escape down Port Road86 to reach Gowanus Creek via a path that I believe would take them almost past what’s now The Ripped Bodice but by the afternoon, the way was only kept open by the coverage the Maryland 400 provided. When the bridges over the creek burned, they waded through the water. There are not a lot of moments where I think things were better in the long distant past87 but I did gasp at the prospect of wading into the Gowanus. In 1776, however, it was still a creek, though the colonial government had passed legislation allowing it to be expanded into a canal in 1774. In 1860, the work to dig Gowanus Creek out and connect it to the bay to better accommodate the industrial and shipping needs of the growing city of Brooklyn was finished. The ratio of industrial waste88 and flow-through water89 poisoned the canal. The smell was bad enough that calls for clean-up began as early asthe 1890s. The Army Corps of Engineers were brought in in 200290 and it was declared a Superfund site in 2009. The main battle ground currently is zoning91 as proposals keep popping up that would reduce taxes for developers building condos and move all the affordable92 housing to where the sewage is still buried.

In total, it was a combination of luck, extreme competency and sacrifice that got the army across the East River as intact as it could be, all things considered. Having learned a lesson from Bunker Hill,93 the British decided to settle in for the night of August 27th rather than push their advantage on an enemy that had proven dangerous when cornered. Rain set in late on the 27th and lingered for two days, which gave the Americans time to plan and execute. The Marblehead Mariners, the Massachusetts 14th under the command of John Glover94 crossed back and fourth eleven times in order to bring over all 9,000 men plus horses and equipment, putting cloth on the horse hooves and ships’ oars to move as silently as possible. Fog came in as the sun rose on Thursday, August 29th, which helped cover the escape of the men who had stayed behind to make it appear their camp had not been abandoned.

The point of departure is the Pier 195 ferry terminal by Brooklyn Bridge Park. By all accounts,96 Washington was the last person able to retreat to board a boat. I don’t know if he turned back to Brooklyn to consider those being left behind or if the smoke over the battle field twirled into the fog or if his eyes were looking forward to the next shore and the next battle, but if you turn back now, you can see the old Brooklyn Eagle building.97

Washington landed around what we know as Pier 11/Wall Street. Fort George at the battery was still in American hands but everyone was acutely aware that they had just fled an island to a smaller island, and the British Navy still existed, so they pressed north.

Howe faced a non-rain delay in his pursuit of the continental army waiting for supplies to arrive by ship at Kips Bay in the form of Mary Lindley Murray. Mary Lindley Murray had been born to a large Quaker family in Philadelphia but by 1776 was living in the Inclenberg98 area north of the city, but it’s 1776 so “north of New York City” means what’s now 35th and Park. Mary Lindley Murray believed in independence and her husband, a successful merchant named Robert Murray was a Loyalist, which seems like it would make dinners awkward but is a decent way to cover your bets against all outcomes. In 1775, Mary Lindley Murray had intervened to ensure that her husband’s politics didn’t get him banned from the city, and in 1776, Robert Murray’s politics were enough to keep the family safely at home as the British took over. And home on Park Avenue meant being close enough to the East River to see the British ships dock and far enough west to see that General Putnam and around 3,500 men who were the rear of the column retreating north, were still making their way up from Wall Street and near enough to be caught. That they were, in fact, on a hill99 also helped their vantage point. So Mary Lindley Murray and her daughters invited General Howe for tea while her maid kept watch at the window to ensure Putnam’s men were in the clear. Mary Murray’s delay is notable both because I’m not sure how many honeypot schemes involve literal honey pots and also because when we talk about history repeating itself first as tragedy and then as farce, I don’t usually think of that as being part of the same military action.

Robert Murray’s vast estate gave its name to land around it, becoming known as Murray Hill.100 PS 116, the Mary Lindley Murray School, opened on 33rd between 2nd and 3rd Avenues in 1868, but full disclosure: I can’t find when it was named after her. The Murray heirs used what weight they had to keep growth limited and residential, which meant the neighborhood became an enclave for the rich and private. Starting in 1902, JP Morgan’s library was built one block west by McKim, Mead & White, and in 1924, Fred F. French designed a co-op on the site of Mary Lindley Murray’s fateful tea party. The plaque went up two years later.

In September, after a few unproductive summits and on the advice of his generals,101 Washington ushered his men further north through McGowan’s Pass on the north end of what is now Central Park and what was then probably an apple orchard.102 Howe would take the same route shortly after, but he stopped at the Black Horse Tavern on the Pass first for the night.

Both were owned by Daniel McGowan, who had made enough money in lower Manhattan as a peddler to move up to Harlem and buy the tavern from his brother-in-law Jacob Dyckman in 1756. The tavern was torn down in 1790 by McGowan’s son Andrew, who wanted to build a larger house for his larger family, but the land stayed in the family until they sold it in 1846 to Mount St. Vincent, a convent that ran a boarding school and hospital.103 By then, the seeds for Central Park were already being sown and the rough plans were approved within seven years. After a fire destroyed the buildings still there, the tavern was rebuilt as McGowan’s Pass Tavern, which lasted until 1917. The park starting composting there in early 1980s, so that section is closed to the public although it’s the nature of composting that the public is still benefiting from it.

The retreating Continentals won The Battle of Harlem Heights in September and stalled the British in October at the Battle of White Plains before making it to Valley Forge in Pennsylvania for the winter.

And so ended the largest battle of the American revolution, in a devasting loss for the Americans that opened the door for the victory over the British. The Battle of Brooklyn became something of a double-edged sword, with a bit of “I’m not locked in here with you: you’re locked in here with me.” There were the fires throughout Manhattan that looked like arson and were made worse by the fact that the only people left in the city to fight the fires were sailors in the Royal Navy pulling double duty.104 Nature, like my dog when I’m holding her food bowl, had its own way of getting under foot: New York Harbor is vast and beautiful and when they were around, the oysters were second to none, but the channel is narrow and the sandbars between Sandy Hook and Brooklyn can bottleneck a fleet if the tides aren’t just right. That makes it hard to leave in hurry, like if you were to have compatriots losing battles in Saratoga or Yorktown, especially if you’re panicked about leaving the city undefended.And that fear was real: Washington’s troops and spy rung kept the pressure on, so holding the city was not the boozy break from Boston the British generals had hoped for. On November 25, 1783,105 the British gave up New York and Washington returned, sailing across the Harlem River and riding down to the Battery in a reverse path of his retreat seven years earlier, and receiving a hero’s welcome all along the way. Six years later, he would be inaugurated here.106

Walt Whitman posited that August 27th should be honored as a foundational day in American history as much as July 4th.107 There’s something about this that makes me think of Ben Franklin108 preferring the turkey over the eagle as a national symbol, writing, “he is.. though a little vain & silly, a Bird of Courage and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards.” One wonders where we would be as a nation if we measured our own strength by our commitment to our highest ideals instead of a commitment to pretending those ideals are so fragile they cannot withstand being shaken. If we could gauge victories in mettle and not just medals.109 Who could we be if applied ourselves to acknowledging we were not always right rather than insisting we were? How strong could we be if we did not think we always had to win, and approached sacrifice as something given of ourselves rather than demanded of others? How much closer could we be to the people we like to think of ourselves as if we measured our success collectively? As is plain from the sheer number of plaques we saw today,110 the Battle of Brooklyn is not history that’s brushed over or forgotten, but I’m struck by how close at hand it feels and how much closer it could still be.

And I’m not arguing: for one thing, it’s not wrong and for another thing, I never start a fight with people who drink Dunkin’ for fun.

Gettysburg, Washington Crossing the Delaware, Normandy, when Beyonce invited the Chicks to perform with her at the CMAs.

It’s referred to as both Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Long Island, so I’m going with the one that’s both more specific and has alliteration.

Except for the Confederates, who get all the tackiest participation trophies thrown at their traitorous little feetsies.

Though this is military history and presidential history and specifically Washingtonian history and you know what means… Plaques. Plaques everywhere. Plaques all the way down. Because we commemorate the history we have collectively decided that matters and wars matter to us.

Spoiler.

These newsletters are long, but there are limits, you know?

D.C. thinks there’s more to say on that one, I believe.

Also, just knowing how history worked: I’m sure the British were also smelly. The only thing that smelled better in 1776 than now was the Gowanus and we’ll get to that later.

They said it, Massachusetts, not me.

Consolidation wasn’t until 1898. I have heard some Brooklynites refer to it as The Great Mistake which is extremely Staten Island of them (pejorative).

Named after a Dutch town in Utrecht whose name comes from the words for marsh, “broeck,” and “lede,” or a small stream, and that would eventually, like it’s American cousin, consolidate with neighboring towns.

This covers what is now the Flatlands but also Canarsie.

This covers Bensonhurst, Borough Park, Bay Ridge, and Dyker Heights so it boasts where my mother is from and also extravagant Christmas decorations.

This is the are we know as Williamsburg, Bushwick (clearly), and Greenpoint.

For “Vlacke bos” or flat woodland. It covers Ditmas and Prospect Park, Kensington, and Lefferts Garden. And Flatbush. That’s kind of a gimme.

Gravesend encompassed what’s now Brighton Beach and Coney Islands and so is why we have the Mermaid Parade and both iterations of The Warriors. Also, please send help, I can’t stop listening to The Warriors concept album.

Her name was Deborah Moody, and we are not related. I am just a Deborah who is moody, not a Deborah who is a Moody and I prefer the term melancholic anyway.

Dun dun DUUUUUUUUN.

Brooklyn the Village covered the Brooklyn the Borough neighborhoods we know as Bed-Stuy, Boerum Hill, Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn Heights, Clinton Hill, Crown Heights, Downtown Brooklyn, DUMBO, Fort Greene, Gowanus, Park Slope, Prospect Heights, Sunset Park and Cobble Hill.

Still the village, not the city or the borough.

Spoiler, but a lot of the markers for it now commemorate it as Battle Pass.

Which would eventually link with the village to the east of it, Stuyvesant.

Seems unnecessary, but I have a radiator.

Auden should not be lumped in with the rest of the British being discussed today. The whole war (and the next one) would be water under the escaping army by the time he came to visit.

And just go ahead and put The Crucible in your pocket for a quick moment.

I guess you could say Washington knew the Howe but not the Where or When. I apologize for nothing.

Admittedly, this was before the spy ring was really set up and was part of the lesson of the necessity of a reliable network.

Which was still Paggank, or Nutten Island, and would be until after the Revolution.

I guess Howe had a lot of say in the matter.

Though originally from Salem, Massachusetts. And if that name sounds familiar in that context: his uncle was Thomas Putnam, one of the main accusers during the Salem Witch Trials, and certainly the accuser most interested in Giles “More Weight” Corey’s land.

You probably didn’t need me for that one but I’m a completionist. The fort had been by General Nathanael Greene, hence the name.

To be clear/more confusing, this is not named for Israel Putnam but his cousin-once-removed, Rufus Putnam, who built it.

Stirling was actually a born and raised New Yorker of aristocratic Scottish descent: his father had fled Britain after taking part in the Jacobite rebellion, which may also be why William Alexander’s attempts to claim his ancestral title of Earl were rejected.

It’s where Fort Stirling Park is now, and again – I’m just saying it so you know you’re right.

Also built by General Greene.

It’s down. The Bronx is up.

Hamilton was stationed in Manhattan this particular summer.

I guess they got lazy when they ran out of generals and builders for namesakes.

Gowanus is named for a Canarsee sachem, Gouwane, which means “the sleeper.”

Et tu, Nathan’s?

Nice.

Including Brits and Hessian mercenaries.

???? Do I just say Masshole?

And the Bronx, which is on the mainland but does have a lot of beautiful coastline.

The song is, after all, “Rule, Britannia! Britannia, rule the waves!” not “Charm, Britannia! Brittania, convince other people to ally with you based solely on the power of your wit and good manners!”

You’re welcome.

When you find a naming convention that works, you stick with it. Otherwise you end up “Orb Fort” and no one wants that. It’s embarrassing.

They all seem like a lot for 2 AM, you know?

Technically, double-gun point, as they held Howard’s son 16-year old, also named William, hostage too for good measure.

The William Howards? The Williams Howard?

He would take a lot of flak for not fortifying the pass, as would Putnam, who didn’t hold a high leadership position ever again.

Troup was later released, fought at the Battle of Saratoga, and lived long enough to become an even greater threat to the city than Howe: a real estate tycoon. Point is, he did fine for himself.

Not rural as in “no, seriously: it’s very woody” but rural style as in part of the shifting attitudes around death that marked the nineteenth century and the growing trend of non-denominational gravesites that served a civic purpose as parkland for the living.

Including Bill "Bojangles" Robinson.

It feels extremely unnatural to root against a General Grant but here we are.

They tell you breakfast is the most important meal of the day but they don’t tell you how dangerous it is.

Which ran up along the shore from Bay Ridge which was still known as Yellow Hook at the time.

Sneaky! And bear this is mind when people say Washington’s tactics were ungentlemanly: it’s all quite out of pocket when the other side does it and terribly clever when it’s your guys pulling the stunt.

Spoiler?

The “H” is for Holden, which was not what I was expecting.

I mean, relatively.

Though Parsons made it back to Brooklyn Heights and would go on to fight in the Battle of White Plains.

A lot of the land beyond 4th Avenue is landfill, so everything used to be a little closer to the water than it is now.

Popular former Mayor and Governor DeWitt Clinton was moved from Albany and reinterred with a flashy monument in 1853.

There’s a special fund to maintain the graves and the records of the soldiers they hold.

And apparently were hoping for only one route at a time, like an action move where the henchmen politely attack the hero one at a time.

From New Hampshire, if you’re into that sort of thing.

Just as well they didn’t remain separate villages, I guess.

He also gets referred to as Von Heister, but now I can’t stop singing his name to “Du Hast” and if that’s where I am, I’m taking as many of you as know Rammstein with me. But seriously: De. De Heist. De Heister.

Last seen holding a gun on the William Howards.

He was released not long after to deliver a message/call for surrender to the Continental Congress and rejoined Washington in time to cross the Delaware with him.

The first, as we covered, is Battle Hill in Green-Wood.

Of Vaux and Olmsted and Central Park fame.

And some artillery, but where’s the pathos there?

Though no more bodies were unearthed.

Cobble Hill actually gets its name from Ponkiesberg, which is a Dutch term for a conical hill which was encircled by cobblestone streets.

An appropriate name for the venue, certainly!

That’s where the hard to spell parts of the name come from.

Its path was later redirected with landfill.

That is a name! Great work, Gist family.

80% of those held in them died from starvation and disease.

They were a great baseball team that vanished completely after 1957. I don’t know what happened. Hope everyone’s ok!

😐

Michael Rawley was a local guy from 13th Street who died fighting in Belgium in 1945.

Or as we call it: First Street.

I like vaccines and voting too much.

So much.

None.

To help clean-up, no one waded in this time around.

Bwah bwah bwah bwaaaaaaaaaaaaaah. Now it’s a party.

Or “affordable.”

Was it a great lesson? Maybe, maybe not, but they learned it!

No relation to the actor.

Not the design store, though there did used to be a Pier 1 where there’s now a TD Bank where Hale was hanged.

Which is a fairly decent number of accounts. Everyone loved talking about Washington.

And an ice cream store, but that’s doesn’t call back to the opening of the Old Stone House.

It’s Dutch for “Beautiful Hill.” I enjoy that it’s singular, because it leaves the open question: is there only one hill or are there other hills but they’re all super basic?

A beautiful hill!

Still only one hill.

Including Nathaniel Greene, who had been around for the fort building but so ill he had been replaced before the battle.

It would likely have been where the Conservatory Garden is or the Museum of the City of New York.

And also why this corner of the park is called the Mount.

Any New Yorker will tell you there’s a cost to be paid to live here. Usually though that’s less arson and more the high rents, bad mayors, and the smell in August.

Coming up soon if you’re reading this around when it comes out: perfect timing to plan pre-Thanksgiving Evacuation Day cocktails! Coming back eventually if you’re getting to this later, but honestly: when you remember that over 50 national Independence Day celebrations across the globe are specifically celebrating independence from Britain, it’s kind of always Evacuation Day somewhere.

The only other president to have that honor was Chester A. Arthur and there were a lot of reasons for that.

This was closer than just how much he viscerally believed in American democracy: he had a great-uncle believed to have been killed that day.

Our sluttiest founder and I think that’s great.

Except for Simone Biles, who obviously has both in abundance.

Plaques. Plaques. Plaques. PLAQUES. PLAQUES. PLAQUES! PLAQUES! (Are you cheering and clapping with me?)