It is one of the great ironies of the single story myth1 that it is damaging in a myriad of ways.2 On an individual scale, it can blind us to the multitudes those around us contain,3 even if we know full well that one scratches a lover and finds a foe.4 In the best-case scenario, it makes us smaller and meaner than we are. In the worst and more common cases, it whispers to us that our worst selves speak truth. Which all brings us to the long, strange afterlife of Dorothy Parker. Now, I would never insult your intelligence by telling you who Dorothy Parker is - I know you're brilliant5 but there’s usually room for a wider perspective.

And I’m not arguing everything you know about Dorothy Parker is wrong. It’s probably not!6 She was clever and stylish, she was an alcoholic, she struggled with suicidal ideation.7 She was also actively committed to antiracism. That tends to get lost in her legacy, possibly because it holds us as the audience to a very different kind of account then her poems of love, pain, and whisky sours for breakfast or it’s just not seen as being as fun. The simple, perhaps less cynical8 answer is we put people in labeled boxes for the same reason we do so with papers or the various doodads that get collected and then put away: it’s easier. The boxes, however, tend to get smaller and smaller depending how far away from being a white man you are, and the labels can loom even larger, until the whole of a woman’s legacy seems to fit into a coupe glass. After her death, her friend Wyatt Cooper9 wrote in 1968, “Biographies will be written about her, then more will be written after that, and people will say they’re marvelous and maybe they will be, but I’m willing to start taking bets that they won’t get anywhere near the truth of her. How can they? The truth of her was that complex, and complex truths resist examination. They play tricks on you. It’s the problem anybody has who sets out to describe any unique personality.”

She was born Dorothy Rothschild10 on August 22nd, 189311 to Jacob Henry Rothschild12 and Eliza Annie Marston Rothschild, the youngest of four by enough years that one might consider her a Happy Surprise. Her family was living on Upper West Side, but she was born in New Jersey as her family had been vacationing on the Jersey shore when Baby Dottie made her appearance in the midst of a hurricane.13 Jacob and Eliza Rothschild had grown up near each other but as she was of Scottish descent and he was German-Jewish,14 her family did not approve of the match for quite some time, though she waited them out teaching in New York. In their familial division of labor, he made good money in the garment industry and she was the more loving and affectionate parent. When she died shortly before Dorothy’s15 fifth birthday, it was a devastating loss.

Around this time, the family had moved to West 68th Street, a pretty street that would become the background for one of Parker’s formative political memories. Looking back from 1939 for the Leftist magazine The New Masses to answer what she was doing to fight fascism16 she described a memory from around this time.17 In the midst of a ferocious blizzard, her wealthy aunt remarked on the good fortune of the storm creating work for the men shoveling snow in the bitter cold. Parker recounts not understanding—either as a child or a grown woman—how it could be good or good fortune for men to have to be exposed to that kind of harshness in order to live: “that was when I became anti-fascist, at the silky tones of my rich and comfortable aunt.” Around two years after that snowstorm, J. Henry Rothschild remarried, to a woman named Eleanor Frances Lewis. She and Parker did not get along: Lewis was quite Protestant and very concerned with the unsaved souls of her stepchildren, sending Parker and her sister to a strict Catholic school.18 Parker, in turn, refused to call Lewis anything other than “the housekeeper.”19

They would not have long to torment each other: Lewis died in 1901. The family as it stood moved a little further uptown to West 80th, though the happiest members may have been the family dogs, who appreciated the proximity to Riverside Park. Dorothy and her sister were sent to Miss Dana's School for Young Ladies, a finishing school20 in Morristown, New Jersey which, ironically, Parker did not seem to have finished. She would have been back home when Rothschild lost a brother on the Titanic21 and died himself in 1913. This may be a spoiler, but he was buried next to Eliza in his family plot at Woodlawn Cemetery. 22

On her own and with not much money, Dorothy Rothschild moved into a boarding house on 103rd and Broadway on what is now Humphrey Bogart Place23 which is not to be confused with Norman Rockwell Place across Broadway.24 She worked in a dance studio and in 1914, sold her first poem for $10: “Any Porch” to Vanity Fair. The poem is snippets of conversations of upper crust women, of not needing the vote, or servants wanting too much, and impressed Vanity Fair editor Frank Crowninshield25 so much he hired her to write captions and copy for Vogue. She started to develop her style, both in clever one-liners—including “Brevity is the Soul of Lingerie” for an ad—and in clothing, as she got a taste for designer clothes. This is also when she met26 Edwin Pond Parker II. She described him as “beautiful, but not very smart” though, as she was known for saying men should be “handsome, ruthless, and stupid,” that might have been a compliment. Less complimentary was his family: his grandfather apparently had a habit of loudly praying for “the unbeliever in our midst” when not referring to her as the “stranger within our gates.” They married in 1917 just before he shipped off to World War I,27 living on West 104th and then West 57th.

Also in 1917, P.G. Wodehouse took leave from his gig as theater critic from Vanity Fair.28 Crowinshield moved Parker29 up and over to fill in, becoming New York’s only female theater critic. Parker’s colleague at Vanity Fair and later the New Yorker, Robert Benchley, described the house style as the “elevated eye-brow school of journalism. You can say anything you want as long as you say it in evening clothes.” And Parker’s barbed wit was a perfect fit. To ensure she’d have an apt target, she would often make a point of seeing shows she did not think she would like, just so her reviews would be razor sharp and especially notable. She expressed some regret for that later in life30 which is an arc that should feel very familiar to anyone watching the rise of social media and seeing the shortcuts to gaining clout. Eddie Parker came back from the war in 1919 but their marriage didn’t in any meaningful way: not to understate things but World War I was a profoundly mass-traumatizing event and Eddie Parker was not exempt.31 He self-treated with alcohol and drugs and cruelty to his increasingly celebrated wife.32 They wouldn’t officially divorce until 1928,33 but she kept the name Parker as she continued to build her career.34

And Dorothy Parker was taking her name far. She was the toast of the town, despite it being Prohibition.35 Her one-liners spread in papers across the city through the columns of her companions at the Algonquin Round Table, an assortment of writers coming together for lunch at the Algonquin Hotel on West 44.th36 It had begun as a welcome home lunch for Alexander Woollcott, a theater critic returning from spending the war writing for Stars & Stripes, but the group enjoyed each other enough to keep coming back. The Algonquin had the advantage of being down the street from many of the major publications its members were writing for and clubs they may have also been members of. Her wit and witticisms were truly an early kind of viral meme. Shakespeare gets a lot of credit for creating phrases we still use today but Parker is if not the inventor at least the first person to put on paper phrases like “high society,” “what the hell,” “one night stand,” “pain in the neck,”37 “boy meets girl,” and “with bells on”38 and “facelift.”39 Looking back in interviews from 1959 and 1966, she would say, “These were no giants. Think who was writing in those days, Lardner, Fitzgerald, Faulkner and Hemingway. Those were the real giants. The Round Table was just a lot of people telling jokes and telling each other how good they were. Just a bunch of loud mouths showing off, saving their gags for days, waiting for a chance to spring them… There was no truth in anything they said: they came there to be heard by each other. It was the terrible day of the wisecrack. So there didn't have to be any truth.” Truth, of course, has never been a prerequisite for glamor or popularity.

Parker could, however, get caught in her own barbs. In 1920, P.G. Wodehouse came back from his leave and Vanity Fair took it as opportunity to fire her: her critiques had often been savage enough to garner attention but not enough to make up for the irritated producers complaining that harsh reviews were running beside the expensive ads they had purchased. Two of her fellow Round Table members, Robert Benchley40 and Robert Sherwood, quit in solidarity. In March, she started writing theater criticism for Ainslee’s Magazine, a monthly magazine with covers full of Gibson Girl-style illustrations and young men in Arrow collars. In the October issue, after praising W.C. Fields and Fanny Brice in the latest Follies, Parker includes a review of a play called Come Seven. It was blackface comedy written by Octavus Roy Cohen, a white writer who specialized in telling Black stories first for the Saturday Evening Post and then as plays performed by a white cast in burnt cork make-up. Parker called it out, writing,

The program is insistent to the point of violence on the fact that all the parts are played by white actors appropriately tinted for the occasion, but it seems superfluous to call attention to this, for one is never in the slightest doubt about it. The actors’ portrayal of the negro race goes only as deep as a layer of burnt cork, and so, one cannot help but feel, does the author’s… The characters who appear in it are not of the colored race, but of the blackface race–the typical stage negroes, lazy, luridly dressed, addicted to crap shooting, and infallibly mispronouncing every word of more than three syllables.

She goes on to write that, “Mr. Cohen is immeasurably to be praised for bringing to the stage the first fruits of a field which would prove amazing fertile for the native playwrights.” By modern/almost any reasonable common sense standards, writing that having Black writers tell Black stories is better than racist tropes is a low bar to clear, but I’m afraid the context isn’t common sense, it’s white America in 1920. Five years before Parker wrote that review, the biggest director cast the biggest movie stars in The Birth of a Nation, a piece of not-even-veiled KKK propaganda. America was moving fast towards the highest membership in the Klan, and it was not coming from the south: it was northern cities like Chicago, Detroit, and New York where antiblack racism was snarling against the Great Migration and a broader white supremacy was lashing out at immigration. Also, Prohibition may not have done much to drain the glasses of Parker and her drinking buddies but the Venn diagram of the Temperance movement and recruiting white women into the Klan has some overlap.41 The trouble with approaching history with the main metric as The Standard of the Day is that it lowers the definition of decency past recognition. The Golden (Girls) Rule, however—where you can see a basic consideration and thoughtfulness being voiced as ahead of its time even when it’s not enough for where we are and need to be—is much more productive. I guess what I’m saying is picture it: the Algonquin Hotel, 1924…

Parker moved into a suite on the second floor of the Algonquin in 1924. In 1925, Round Table friend? Guest of honor? Harold Ross and Jane Grant42 started The New Yorker in offices down the block on west 44th. Parker was one of the founding writers. A year later, her collection of poetry, Enough Rope, was published to great acclaim. In the 1927, Parker wrote a short story for The New Yorker called “Arrangement in Black and White.”43 It aims the relentless specificity of Parker’s prose44 against a woman not as liberal as she congratulates herself on being, with a sharp slice Dick Gregory-observed northern racism.

In the spring on 1927,45 Parker and another member of the Round Table, Ruth Hale, went up to Boston to protest the coming execution of Nicolo Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.46 She was arrested for Loitering and Sauntering but only held in jail for a few hours and released after paying a $5 fine, which would be a little over $90 today, which isn’t a latte but it still isn’t a lot, if you’re with me, and does seem to have been enough for the FBI to start a file on Parker.

1929 saw the publication of “Big Blonde,” Parker’s O. Henry award-winning story of Hazel Morse, a one-time model/aging party girl struggling against weight of always being a “good sport.”47 Edwin Parker died in 1933, though it was uncertain if the overdose that killed him was an accident or not. The Round Table didn’t really survive into the Depression, although when Dorothy Parker moved to East 52nd near Sutton Place in 1934, she was right next door to Alexander Woollcott, the writer whose welcome home lunch had sparked the group to begin with.

Beyond the new apartment, Parker had also met Alan Campbell, a writer and actor who would become her screenwriting partner as well as her second and third husband. He was eleven years her junior, tall and handsome.48 They headed out to California to try their shared hand at Hollywood, where the social scene was different but the money was good. They were being offered $1,250 a week as a team49 which was a staggering $28,000 now. It was enough to cover debts in New York, get a house and household staff in LA50 and a place in Pennsylvania. Parker didn’t love the work but they made a good team, with Campbell focusing on areas Parker struggled with51 to enable her to play to her strengths. In LA, Parker renewed her friendship with Dashiell Hammett, whose books she loved and whom he’d met at a party in New York, and his partner, Lillian Hellman. Hellman had met Hammett when she was a young (and married) script reader at MGM in 1930. She did not take kindly to Parker at first –she found Parker’s effusive praise of Hammett’s work to be too much—but they would become friends. It seems to have helped that the success of The Children’s Hour in 1934 moved Hellman from Hammett’s Young Plus One into a known quantity in her own right, but it was also meaningful that they shared not only writing52 but politics.

Parker herself had felt the boost of solidarity after her firing from Vanity Fair in 1920, even though her friends quitting was largely a symbolic protest, and in Hollywood she paid that forward with interest. The Screen Writers Guild had been formed over the course of the 1920s and then severely undercut by Louis B. Mayer and had been largely inactive for years. Parker, horrified by the practice of writers being made to work on spec,53 joined a group of ten writers that included Donald Ogden Stewart54 working to revive and expand the guild. Parker was an active recruiter and poured her energy and clout into the cause. Parker threw herself into things to the point of falling out with Round Table friend Robert Benchley over his lack of interest. The initial group grew to include Ogden Nash, and Hammett and Hellman among others, but the biggest assist came from back east: New York Senator and Goddamn Hero Robert Wagner. In 1935, Wagner55 got his National Labor Relations Act through the senator onto FDR’s desk to be cheerfully signed. The Wagner Act, as it would be known for the very obvious reason that Senator Wagner wrote it, created the National Labor Review Board, asserts the right of employees to unionize for protection and collective bargaining without retaliation, and sets enforcement mechanisms and processes. The Wagner Act, aside from just being objectively very good, meant that when studio bosses tried to form their own writer’s union to negotiate with, the SWG went through the NLRB and were affirmed as the chosen agent for writers.56 It was a major success, just in time for the union and its most prominent advocates to be smeared as commies and looked into by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

In 1936, after attending a dinner party with Donald Ogden Stewart, Frederick March57 and Oscar Hammerstein where Otto Katz58 spoke about the dangers of Nazism, she signed on as honorary chairman of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. Many friends tended to roll their eyes at her activism or sneered that she must be drunk, but one group very happy to take Parker seriously was the government, mostly because most of her causes were considered suspiciously socialist.59

Having made her “I Think Fascism Is Bad, Actually” stance quite official,60 in 1937, Parker went to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War.61 This would inspire her short story, “Soldiers of the Republic,” which came out in The New Yorker the following January but she offered her non-fiction thoughts to The New Masses first. It’s hard not to read her account and not feel her to be changed:

I heard someone say, and so I said it too, that ridicule is the most effective weapon. I don't suppose I ever really believed it, but it was easy and comforting, and so I said it. Well, now I know. I know that there are things that never have been funny and never will be, and I know that ridicule may be a shield, but it's not a weapon.62

She describes the streets of Valencia after German planes had dropped their bombs on civilian streets:

There was an old, old man who went up to every one he saw and asked, please, had they seen his wife, please would they tell him where his wife was. There were two little girls who saw their father killed in front of them, and were trying to get past the guards, back to the still crumbling, crashing house to find their mother. There was a great pile of rubble, and on the top of it a broken doll and a dead kitten. It was a good job to get those. They were ruthless enemies to fascism.

She gave and raised money for refugees and continued sounding the alarm on Nazism. 1937 also saw the release of the first A Star Is Born,63 which Parker and Campbell would receive Oscar nominations for their screenwriting.

When World War II broke out,64 Parker tried to be of use but found herself rebuffed. She was rejected from the WAC for being too old. She applied to be a war correspondent but was rejected, classified as PAF, or Premature Anti-Fascist, which is just huge “I can forgive anything except someone being right” energy.65 In 1943, she published the short story, “The Lovely Leave,” about a young wife full of strain and anticipation and regret over her pilot husband’s brief visit home, for which she was slammed as being unpatriotic. She also published the poem “War Song,” in the New Yorker, like a shadow reflection of her 1928 poem, “Penelope.” Alan Campbell joined up in 1942, at Parker’s urging/scorn for not having done so yet. They divorced in 1947 –the same year as Parker’s second Oscar nomination—but remarried in 1950.66 Parker and Campbell would separate again in 1952 but stayed married until his death in 1963, which, like Eddie Parker’s, was a result of an overdose that no one is quite sure was intentional or not.

But before the dark times of Campbell’s death are the dark times of McCarthyism. Paker was never formally called before HUAC, but the power of authoritarianism lies in its ability to get interested parties to obey in advance. Outside groups listed Parker as a communist and that was enough for the work to dry up. It didn’t matter that the government only ever pointed to Communist adjacent groups:67 she had been accused; she was guilty. She collaborated with Arnaud D’Usseau on a play called The Ladies of the Corridor68 about women of a certain age in a New York residential hotel facing the back-half of their lives without their husbands and unsure of their purpose69 but a major chapter of her life and career was closing fast.70

So, widowed and blacklisted, Dorothy Parker returned to New York. She moved into the Hotel Volney on East 74th Street, where she’d lived previously when she’d been in need of a change of scenery. It was a strikingly similar scene to The Ladies of the Corridor: society women alone and waiting to die. Parker would often crack that the hotel had a secret chute to transport residents to the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Home when they passed.71 She wrote book reviews for Esquire and some columns for The New Yorker, making enough to take care of her and her poodle, Troy, but not earning all that much. She did some interviews, notably with her friend Wyatt Cooper and Richard Lamparski, and she read and she drank. To Lamparski, she spoke glowingly of Truman Capote72 and James Baldwin. She saw Beatrice Ames, the ex-wife of her longtime friend Donald Ogden Stewart,73 quite often and Lillian Hellman quite seldomly.74 This was the state of things when in 1965, she called her attorney to set up her will: no spouse, no children,75 her friends seemed to be doing ok but the causes she believed in were struggling. So when Oscar Bernstein came over to her place to put her affairs in some kind of order, she left the entirety of her estate (around $20,000 which would be about $188,00 now) to Martin Luther King. They had never met—this isn’t a story of his intersection with pop culture like when he convinced Nichelle Nichols to continue on Star Trek past the first season—she just believed in his work. After his passing, she left the entirety of her estate including future royalties to the NAACP. The future royalties is significant because the collection of her work sold with a yellow cover as The Portable Dorothy Parker?

That hasn’t been out of print since it was first published in 1944.76 She named her dear friend and comrade Lillian Hellman as her executor, in charge of her archive. The funeral shouldn’t have been too big an ask: she wanted “no funeral services, formal or informal,” just a quiet cremation. Parker died in her room at the Volney on June 7th, 1967.

Hellman had, to be a bit blunt, expected to inherit Parker’s estate. They had been friends for decades and Hellman would have known she had no family. Hellman, it’s worth saying, was doing fine for herself: she had inherited Dashiell Hammett’s estate and control of his work when he died in 1961, she owned her townhouse on East 82nd and also a place in Martha’s Vineyard. She had been able to continue working on Broadway and did find her way back in Hollywood77 despite being accused of being a Communist on the same lists as Parker. By the time of Parker’s death, Hellman was working on her memoirs, though obviously Parker couldn’t have known how popular they would become.78 Point being, she saw her friend getting by and entrusted her with her artistic legacy. Talking to friend and writer Howard Teichman, Hellman was said to have described Parker’s bequest thusly:

That goddamn bitch Dorothy Parker. . . You won’t believe what she’s done. I paid her hotel bill at the Volney for years, kept her in booze, paid for her suicide attempts—all on the promise that when she died, she would leave me the rights to her writing. . . But what did she do? She left them directly to the NAACP. Damn her!

Well then. It’s got that ‘Nice Guy’ Complaining He’s Been Friend-Zoned Because He Thought Basic Decency Earned Him Sex vibe but with money. She was especially put out because she did not like MLK, finding him to be pompous and complaining that he reminded her of the preachers she encountered growing up in the south.79 The trouble is, when you’re gone, it’s your executor who is meant to speak for you and see your wishes through, and Hellman seemed more in a speak ABOUT Parker than FOR her kind of mood.80 It began with the funeral that Parker didn’t want. Held at the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Home, just like in one of her jokes, she was laid for all the world to see in a brocade gown81 in a large and speedy affair.

Obviously, funerals are for the living but if we take death as an inevitable part of life, it is difficult to claim we had a life fully freely lived if we are not free to claim the death we deem most dignified. Hellman spoke about Parker’s legacy and in his eulogy, Zero Mostel made a crack about how even Parker, the guest of honor, would rather not have been present. Parker’s niece and nephew were initially disappointed and considered asking MLK to share the estate, but instead asked Hellman for keepsakes—an autographed book or picture to remember her by—as well as her final resting place but never heard back.82 But that brings to her final resting place, and that story is almost as long as her life.

King, it should be said, had maybe not heard of Dorothy Parker at the time of her death.83 When told of her will, he told the SCLC colleagues he was dining with: “This verifies what I said, that the Lord shall provide.” He would speak very warmly of what it meant for a stranger and a white woman to believe so strongly in what was right, she would give all she had. King was not given much time as her heir, as he was assassinated only ten months after Parker passed.

Parker was cremated as she’d requested. She was taken care of on June 9th, 1967 at the Ferncliff Crematory in Hartsdale, New York.84 And then she stayed there. For six years. Hellman had left no instruction for her remains, so she was stored on a shelf at the crematory. Her belongings had been rather unceremoniously tossed from the Volney. Hellman seemed to comfort herself for losing out on the purse by tightening the metaphorical purse strings on Parker's archive. She took her position as literary executor rather zealously and everyone got rebuffed: the Library of Congress, a proposed revue with Cole Porter’s music and her poems as lyrics, biographers. She would even warn mutual friends not to speak to would-be biographers. One rather sharp interpretation is she was concerned Parker’s diaries would contradict her own memoirs. There are other explanations offered by different people but they’re not actually more generous and we haven’t even hit the court case yet.

King’s assassination meant Parker’s estate went to the NAACP, but it also meant control of her archive went with it. Hellman took exception with the second part and went to court to argue control should remain with her. She lost her case in 1972. Not unrelatedly, she stopped paying the storage fees to the crematory that was still housing Parker’s remains. She gave them no further instructions, nor did she alert any family or friends to have the take over. Uncertain what to do, Ferncliff shipped the urn to the Parker’s lawyer’s office, O’Dwyer and Bernstein.85

Oscar Bernstein had retired by then86 so his client went to Paul O’Dwyer in a very literal, physical way. And that’s where she would stay for fifteen years, sometimes displayed on a shelf, sometimes in a file cabinet, sometimes being brought out for guests. But in 1973, Parker’s urn was still newly arrived downtown and Hellman had a new memoir coming out and was doing an interview with Nora Ephron in the times to promote it. Ephron inquires about the Parker estate and Hellman says, “It's a bad story. She left everything to Martin Luther King, and on his death it was to go to the N.A.A.C.P. It's one thing to have real feeling for black people, but…”

I just want to pause there and ask Hamlet VIII the Algonquin Hotel Cat for a ruling on how it sounds when white people start to profess support for Black people and then throw in the word “but.”

Apologies, that was rude of me to interrupt. She goes on to say, “It's one thing to have real feeling for black people, but to have the kind of blind sentimentality about the N.A.A.C.P., a group so conservative that even many blacks now don't have any respect for, is something else. She must have been drunk when she did it.” Ironically, later in the interview, when explaining her thoughts on feminism, she states, "It's very hard for women, hard to get along, to support them selves, to live with some self respect. And in fairness, women have often made it hard for other women." I did read one piece recounting the estate fight that quite derisively described Hellman as wantonly seducing every man in her vicinity even into her sunset years despite not being especially pretty but honestly: it's too late to get me on her side.

Anyway, Lillian Hellman’s Pentimento was the only book to come out in 1973. That year, The Portable Dorothy Parker was re-printed and expanded. There’s a decent chance this is the edition you know, iconic yellow cover and absolutely baffling introduction by critic Brandan Gill.87

Recovery of Parker’s ashes really began with her biographer, Marion Meade, when she was researching Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell Is This? that came out in 1989. She visited Paul O’Dwyer in 1987 and mentioned she was going up to the crematory to pay her respects when O’Dwyer brought Parker out. He explained that he’d been holding on to her while waiting for instruction from Hellman.88 Meade thought of taking the ashes to Woodlawn, where Parker’s family plot is, but O’Dwyer reached out to gossip columnist Liz Smith and asked her to put out a call for suggestions for a more appropriate resting place than his filing cabinet. They had a meeting/cocktail party at the Algonquin to discuss. Some suggested a shrine at the Algonquin, though the owner wasn’t supportive of that one, a chopper pilot offered to spread her ashes over the Hudson,89 someone wanted to snort the ashes,90 and one person wanted to turn the ashes into paint and use that to paint a portrait of her, which is extremely meta. None of Parkers surviving family members had heard about the meeting or were extended an invite. The idea that won the day came from Dr. Benjamin Hooks, executive director of the NAACP. He pushed for something that would honor the whole of Parker’s life and suggested a memorial garden at NAACP’s national headquarters in Baltimore, saying, “The idea of a white woman leaving her entire estate . . . to the black cause was unparalleled. I can imagine the gesture was greeted with a raised eyebrow by many whites.”

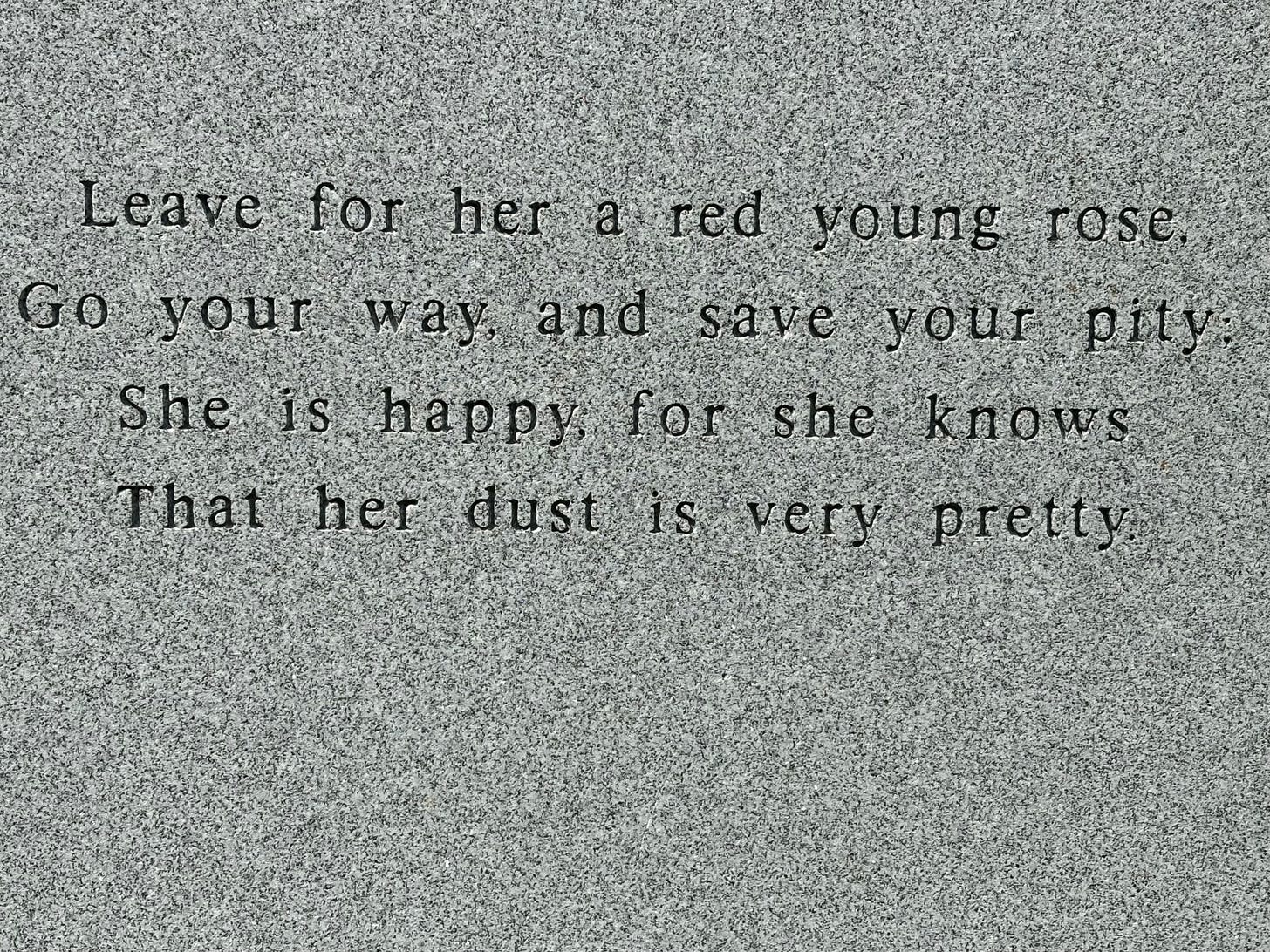

And so October 20, 1988, Dorothy Parker found her third final resting place, in Baltimore. Amid a circular brick seal, the epigraph read:

Here lie the ashes of Dorothy Parker (1893-1967) Humorist, writer, critic, defender of human and civil rights. For her epitaph she suggested “Excuse My Dust”. This memorial garden is dedicated to her noble spirit which celebrated the oneness of humankind, and to the bonds of everlasting friendship between black and Jewish people.

It was a thoughtfully chosen and well-designed plot, though a little out of the way for many of Parker’s visitors and an office building next door blocked the view for passersby. But in 2006, the NAACP was preparing to move to DC and the question of where Dorothy Parker would go was again raised. This time the mantle91 was picked up by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the tour guide and author who founded The Dorothy Parker Society. Fitzpatrick brought in Parker’s suriving family members and coordinated fundraising—including crowdfunding and the New York Distilling Company doing a special release of their Dorothy Parker gin, Dorothy Parker Round Table Reserve Gin—to cover bringing Parker back to New York and setting a headstone for her in her family plot at Woodlawn Cemetery. And then he went to Baltimore and literally brought her back, handcrafting a box to hold her urn and taking her home on the train in the summer of 2020. The unveiling was the following August, presenting with music, recitations, and gin.

The epitaph is from a 1925 poem of hers, “Epitaph for a Darling Lady,” the last of its three stanzas. If you’re in New York, you can pay your respects, and if you’re in New York and it’s not yet August 18th as you’re reading this, you can take a tour at Woodlawn through the Dorothy Parker Society.92

Parker’s internment is a little more recent than would normally be featured in this newsletter, but I was working on the assumption that between the pandemic and the election, maybe it fell under people’s radars. And admittedly, the north star of this newsletter is the hidden history of the buildings we walk by everyday but that can be as true for people and what we think we know of them. Walt Whitman made a very good point when he proclaimed to be large and contain multitudes. We all can. And that can be optimistic but also terribly cruel. In the Wyatt Cooper profile of Dorothy Parker, he recounts speaking to Lillian Hellman of Parker: “When I told Lillian Hellman that she was the one friend of whom Dottie consistently spoke with respect, affection and admiration, Miss Hellman said, “People have told me that through the years and I always found it hard to believe, but so many have said it I’ve finally come to accept it.”” We each of us have the capacity to be so much larger or so much smaller than we seem.

The idea articulated by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie that certain groups of people only get one story told about them.

Like, live by the single sword, die by the single sword?

“Song of Myself,” anybody? Eh? Eh?

On point for our subject!

And good looking! Thanks for reading: tell your friends to subscribe!

Some of the quotes you’ve heard attributed probably are, though: there was a longish period when everything anyone thought was funny was attributed to her, which she did not enjoy because not everything was up to her level. “You can lead a horticulture but you can’t make her think” is real though, coming out of a dinner party game of using words in a sentence.

Which in and of itself can dominate a life: Heather Clark, the author of a still-kind-of-recent and admirably massive biography—in a world of doorstops, be a stepladder!—of Sylvia Plath titled Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Path has spoken quite movingly about what it means to look at a whole life and body of work and turn away from our shared shorthand.

Or perhaps more cynical.

Fourth and final husband of Gloria Vanderbilt and father of Anderson Cooper, which is a separate branch of the Vanderbilt family tree from Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, going back to a different grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt.

Not those Rothschilds. The family was well-to-do but not Spawn-Centuries-of-Antisemitic-Conspiracy-Theories rich.

Leos, amirite?

(I don’t actually know what that means but it seems to work with every sign.)

He sometimes went by Henry Jacob or J. Henry, which seems at least maybe connected to how much antisemitism was around at any given time.

I am politely asking Jersey not to try to claim Parker as she strenuously did not consider herself from New Jersey and honestly, the whole Ellis Island still stings. Is that just me? I can’t be the only petty person lugging around that grudge, right?

Maybe not practicing, but that is rarely a factor when gentiles define Jews.

Dottie in the family home and to her friends but I don’t want to be presumptuous.

Her answer was the title, “Not Enough.”

She puts it in the neighborhood of when she five years old, or when “nobody was safe from buffaloes” which seems to be a favorite self-deprecating age joke.

I don’t know why she went with a Catholic school when she was Protestant except that Parker would describe it as very close to their apartment and did not even require crossing an avenue, and an easy commute is its own kind of heaven.

Ooop!

To be fair, it had a strong reputation for vigorous and progressive academics.

I support you digging deeper into any fact or idea you find interesting but I would caution you against a google search about Rothschilds and the Titanic, which opened up a whole antisemetic conspiracy wormhole I didn’t know existed. And they didn’t even have the decency to make an Iceberg joke.

I don’t know where Eleanor Frances Lewis ended up. Maybe she had her own family plot she wanted to spend eternity in.

His childhood home is on the corner.

He was born there and a group of local high school kids lobbied to have the street named for him in 2016. Which is nice! Good job, Kids Who Are Now Young Adults!

His great-nephew was Ben Bradlee of the Washington Post, which certainly puts the “great” in Great Nephew.

Or at least started: they may have met in their youth at a summer hotel in Branford, Connecticut.

Her new in-laws did not attend.

His eyesight kept him out of the war so I’m not sure of the reason, but he and his writing partner had a series of Broadway shows so maybe he just wanted to focus on lyrics?

And now she’s officially Dorothy Parker! It’s not just that I feel uncomfortable calling her by her first name and find “Rothschild” olddly hard to type.

Mostly towards Katherine Hepburn, whom she described in 1931 as “running the gamut of emotions from A to B” and of whom she would later say there was “no finer actress.” She explained the discrepancy by saying: “Oh, I said it, alright. You know how it is. A joke. When people expect you to say things, you say things. Isn't that the way it is?”

It was also the middle of a deadly, years-long global epidemic and I think we can all agree that that doesn’t do anyone’s mental health any favors.

He, according to Dorothy Parker, “was supposed to be in Wall Street, but that didn’t mean anything.” He worked as a broker for Morton, Lackenbruch & Co. in the Equitable Building which you may remember as being so unpleasantly massive it spawned zoning reform in the city.

Granted on the grounds of intolerable cruelty.

She didn’t miss Rothschild, she said.

See what I did there?

It is worth saying that what we currently call Manhattan is the Lenapehoking, the territory of the Lenni Lenape, who have deep tribal ties to the Algonquins, and the Algonquian-speaking Shinnecock Indian Nation is still centered in Suffolk County on Long Island. There are different stories about how the Algonquin Hotel was named but it was mostly playing off the then newly-opened Iroquois Hotel a few doors east when someone very correctly pointed out the original name, The Puritan, was a buzzkill. This is obviously history too big for a footnote but let us return to the main text on this (unintentional and wholly symbolic) note of a thing being taken from the puritans to be named after the indigenous peoples.

There’s a short story just in that list.

As in “I’ll be there with bells on.”

I came upon this list from The Dead Ladies Show on Dorothy Parker, and if you listen to podcasts or are in Berlin, I can’t recommend it enough.

If that name sounds familiar but in a hazy kind of way, his grandson is Peter Benchley, author of Jaws.

There’s a lot of historical precedent for the woman author and journalist Mona Eltahawy calls “foot soldiers of the patriarchy.”

They were married but I felt like typing “and his wife Jane Grant” weighted things oddly and defined her by him in a one-way street, so now you just get a fun surprise if you read the footnotes.

You can find it in the digital archive if you have a subscription and just going by the number of New Yorker tote bags in the world, a bunch of you do. It’s the September 30th issue.

The opening line is, “The woman with the pink velvet poppies wreathed round the assisted gold of her hair traversed the crowded room at an interesting gait combining a skip with a sidle, and clutched the lean arm of her host.”

Big year for Parker, professionally and politically!

Sacco and Vanzetti were Italian immigrants and anarchists who maybe/probably robbed a shoe company in 1920 and killed a security guard and the paymaster in the process. There’s some ballistic evidence confirmed after the execution that points to Sacco’s gun—if you see a picture of both of them, it’s Vanzetti with the mustache—but there’s also evidence the judge bragged about showing “those anarchist bastards” what’s what, a lot of confessions and recantations, and a lot of questions about who was told what when. And no trial, let alone a capital case, is supposed to come down to “two wrongs could maybe make a right.” So make of that what you will: you’ll probably do a better job than the state of Massachusetts until then-governor Dukakis officially declared the trial unfair on the 50th anniversary of their execution. Back in the 1920s, it was a popular cause for a lot of intellectuals and activists whose politics tilted left.

A sort of spiritual forerunner of the Cool Girl.

Yeah, girl.

$1,000 for Dorothy Parker and $250 for Alan Campbell.

It was a high turnover rate because they drank until late and assumed the staff would be on call.

Like long form never being her bag.

Parker was the one who suggested the title for Hellman’s The Little Foxes.

Doing the work in the hopes of it becoming a job rather than doing the work once you get a job, which does seem the more natural order of things.

A friend from their New York days and the writer of The Philadelphia Story and An Affair to Remember.

Father to then eventual and now former New York City Mayor Robert Wagner, unrelated stranger to Hart to Hart’s/person of interest in the death of Natalie Wood Robert Wagner.

Because management isn’t supposed to get a vote in who they sit across the bargaining table with.

I’m slipping his name in the middle because it’s the one I didn’t recognize but his acting resume is very impressive!

He was a Soviet agent but I don’t think he mentioned that, just on account of how being an agent works.

On the big Is She Now Or Has She Ever Been…? question, she stated in 1937, “I am not a member of any political party. The only group I have ever been affiliated with is that not especially brave little band that hid its nakedness of heart and mind under the out-of-date garment of a sense of humor.” She said it to a lefty magazine, but the point stands.

Again, by the Golden Girl Rule of gauging historical choices, it sounds small but it was ahead of her time. Technically, it’s also ahead of ours, which… is not so great.

Jean Ross, who had inspired the character Sally Bowles back when she was living in Berlin, also reported extensively from Spain, if we're speaking of women remembered for their most gin-scented iterations. I don’t know that Parker overlapped with Jean Ross but she did cross paths with Christopher Isherwood in LA.

She would later warm back up to the idea of humor as a weapon saying, “You can’t just get angry at them. That’s another kind of admiration.”

Not the Judy Garland one, the one before that.

And America was pulled in.

The government wasn’t being persnickety about the bad etiquette of arriving early to a party: PAF was used to screen out suspected socialists.

This is the wedding Humphrey Bogart attended.

Or even that the whole Red Scare was a moral stain, in case we’re getting a bit too bogged down in the “is she or isn’t she?” of it all. It doesn’t have to be America’s original sin or most recent sin to count!

It would rank up there with being arrested for protesting the execution of Sacco and Venzetti as things she would cite being proud of in interviews.

Oh man. What a day to have already used a Golden Girls reference.

Or being closed on her.

If I can go a little Gunilla Garson Goldberg for a moment, they handled Jackie O’s funeral.

Though she had apparently been hurt not to make the cut for the Black and White Ball.

They had divorced when they both decided they would rather be married to the people they were having affairs with, which in her case was Count Ilya Tolstoy, which is a real change of pace from a socialist.

Hellman was said to have found Parker’s alcoholism depressing.

There was a niece and nephew.

It doesn’t have that yellow cover anymore though.

To some mixed reviews. In an interview in 1966 while chatting about film, Parker commented on what a pity it was Hellman’s latest, The Chase, had been so poorly received.

Or how controversial: Mary McCarthy said everything she wrote was a lie, “including ‘and’ and ‘the’” and war correspondent Martha Gellhorn also called Hellman’s account of her time in Spain into question.

That one seems like a feature, not a bug.

Friends, do you remember getting on the subway with a token? Did you see any pre-Force Awakens Star Wars in a theater? How aware are you, right at this moment, of your joints? You should have a will. And really think about your executor. And if you’re only seen subway tokens in the Transit Museum, reach out to older loved ones and make sure you know their wishes. And ask them how their joints are doing.

She did like the gown: it had been a gift from Gloria Vanderbilt for a dinner party she hosted.

She seems to have also blown off a neighbor who said Parker had promised her a fur coat, but that seems somewhat less mournful.

He was born in 1929, which was after the heyday of the Algonquin Round Table and also, he was busy.

It’s about an hour’s drive north of the city, a little west of Scarlsdale.

It’s still around if you need any legal help, FYI.

And would pass on himself the following year.

It opens with a few pages where he seems to think it was very peevish of Parker not to die young like she seemed to want in her poetry, imagines the surprise readers will feel when being told she was famous and respected, and refers to AE Houseman as a “forbidding male spinster” which is certainly A Choice but at least he didn’t refer to Houseman’s lovers as ‘close friends’? He also refers Parker’s slightly melancholy quips about wanting to get married to change her name as “a constant resentment at being Jewish” which is a bit backwards. When one dips and dodges out of the way of antisemitism, it isn’t being Jewish that’s the issue. I don’t want to be snide – that is a mood well-covered by the printed introduction – but it feels like an aggressively Connecticut mistake to make.

Which was definitely not coming at that point as Hellman died in 1984.

Which seems nice!

Maybe sometimes a little kink-shaming is appropriate.

And eventually, the urn.

They also have walking tours, and a terrific website.

Another triumph 💚